One of the most remarkable things about Amanda Foreman's magnificent study of British involvement in the American civil war is both its length – it comes in a few folios shy of 1,000 pages – and also, almost as telling, that virtually no one has commented on this, perhaps out of respect for the fact that Dr Foreman devoted more than 10 years of her life to it. Film, video, TV and radio all accommodate our diminished attention spans, and the fragmentary nature of modern life, but books are definitely getting longer.

There are some precedents here. "Another damned, thick square book," the Duke of Cumberland is said to have remarked to the author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. "Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr Gibbon?" Today, however, Foreman's A World on Fire is just the biggest beast in a menagerie of fatties.

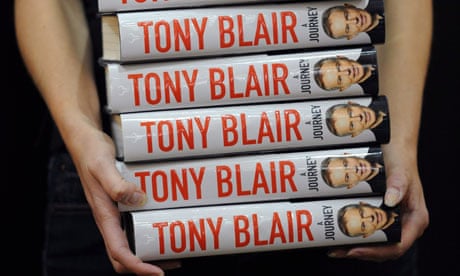

To take a random sample from the current autumn season, Keith Jeffery's history of the secret service, MI6, is more than 800 pages. Tony Blair's A Journey tops 700 pages. Alan Sugar – Alan Sugar! – has an autobiography, What You See Is What You Get, that weighs in at 612 pages, while Orlando Figes's history of the Crimean war is almost terse at 575 pages.

This trend is not confined to non-fiction. Christos Tsiolkas's The Slap is almost 500 pages and Ken Follett's doorstopper Fall of Giants, if anyone's counting, is about 850 pages, probably to appeal to his American readers. Is anyone editing these books? The truth is that they all bear the imprint of marketing, not editorial, values.

Literary elephantiasis starts across the Atlantic. North America has a lot to answer for. In the "pile 'em high" tradition, US bookshops love to display big fat books in the window. The cut-and-paste technology of word processors must bear some of the blame, but overwriting is part of the zeitgeist. Jonathan Franzen's Freedom is highly enjoyable but who's finishing it? The novel is at least 100 pages too long.

Whatever happened to brevity? Once upon a time, it was not just the soul of wit, there was a strong literary preference for the shorter book, from Utopia to Heart of Darkness. More recently, The Great Gatsby, for my money the greatest novel in English in the 20th century, comes in at under 60,000 words, a miracle of compression. The novels of that great triumvirate – Waugh, Greene and Orwell – average 60-70,000 words apiece; even 1984 is not much over 100,000 words.

That neglected genius, Robert Louis Stevenson, used to say: "The only art is to omit." In a letter to a friend, he declared – in words that should be nailed over every writer's desk – "If there is anywhere a thing said in two sentences that could have been as clearly and engagingly said in one, then it's amateur work."

If it's a choice between the tight-lipped or the windbag, give me the aphorist every time. Most novels do very well at about 250 pages or fewer. Seriously, what history or biography needs to exceed 500 pages? Some public-spirited cultural patron – the Man Group, perhaps – should sponsor a prize for short books.

This, by the way, is not an original point of view. As I was researching the history of brevity, I found this, attributed to Samuel Johnson. "Was there ever yet anything written by mere man that was wished longer by its readers, excepting Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe and The Pilgrim's Progress?"

So, before Observer readers weigh in with angry protests, let's concede that War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, In Search of Lost Time, Vanity Fair, Middlemarch and The Portrait of a Lady are all substantial books that earn their length.

Against the bulging library of "damned thick, square books", here's my top 10 of slim volumes:

1. George Orwell: Animal Farm

2. Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea

3. Evelyn Waugh: The Loved One

4. Henry James: The Turn of the Screw

5. RL Stevenson: Treasure Island

6. Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

7. Marguerite Duras: The Lover

8. F Scott Fitzgerald: The Great Gatsby

9. Graham Greene: The End of the Affair

10. Muriel Spark: The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie

Digital Dan brings Nigella into your kitchen

As e-book sales for 2010 approach the magic figure of $1,000m (£622m), Random House has appointed Canongate's Dan Franklin as its digital editor with instructions to go "direct to digital". As well as representing the shape of the future, Mr Franklin is going to cause some short-term internal communications problems. RH already has an authentic Dan Franklin, in the shape of Jonathan Cape's editorial director. Dan the first, however, is not renowned for his grasp of the new technology. His alter ego tactfully says that he looks forward " to helping Random House be at the centre of the digital space." Presumably, this will include exploiting properties such as the Nigella app – the world's first hands-free voice-operated cookery app.

Isherwood gets another leg up from the movies

Ever since Tom Ford turned Christopher Isherwood's gay novel, A Single Man, into a tasty Hollywood confection starring Colin Firth, Isherwood's stock has been rising steadily. FIrst, there was the latest volume of his diaries, and now I hear that the editor of that enthralling volume, Katherine Bucknell, has signed a multi-volume contract with Chatto & Windus for a biography. It won't be the first time Isherwood, who went to Berlin "in search of boys to love", has had help from the movies. In 1972, Liza Minnelli took the role of Sally Bowles in Bob Fosse's Cabaret, transforming the demimonde of Isherwood's Berlin Stories into a glitzy and commercial cinematic hit.