Hunter S Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas famously begins: "We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold." The first sentence of The Bell Jar, by Sylvia Plath, goes like this: "It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York."

But never mind all that. Life & Laughing is the autobiography of Michael McIntyre, the 34-year-old comedian who is now arguably as successful as any standup has ever been. At the time of writing, it has sold 169,210 copies. People like it; at my local WH Smith, it seems to be selling like cut-price gold. It starts: "I am writing this on my new 27-inch iMac. I have ditched my PC and gone Mac . . . It's gorgeous and enormous and I bought it especially to write my book (the one you're reading now)."

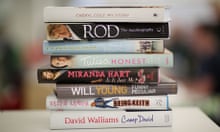

While we're here, consider also the enticing kick-off passage of My Story, by Dannii Minogue: "Having a baby; joyful, a quiet celebration with family. An intimate and magical moment of discovery shared with your partner. Hmmm . . . I wish!" She goes on: "The car is stuck in rainy London traffic and, as usual, I'm running on what some of my closer friends would call 'Minogue Time', which basically means I'm late." This does not quite get me hooked, though I persevere. But more of that later.

To begin The Woman I Was Born To Be, that blessed national treasure Susan Boyle goes for a gnomic statement of the obvious: "My name is Susan Boyle." Cheryl Cole's Through My Eyes commences no less prosaically – "In 2009, we decided to take a break from Girls Aloud. During this time an opportunity came for me to make a solo album" – but it's essentially a picture book, so maybe I should leave off.

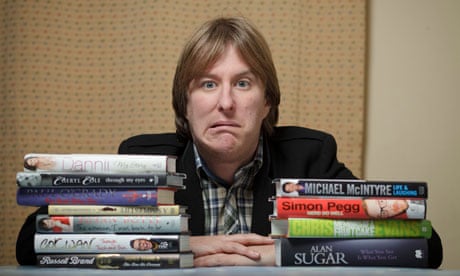

Anyway, these books are not only dominating the bestseller lists at he moment, but my life too. The plan is simple enough: to collect these less-than-literary works, resolve to get beyond the first sentences, and thereby take the national pulse. So, I duly line up the memoirs of McIntyre, Minogue, Alan Sugar, Chris Evans et al – along with the supposed work of a fictional meerkat – and get to it.

First, though, I speak to my agent. Jonny Geller is managing director of Curtis Brown's books division, and down the years he has occasionally sat me down and patiently explained the frazzled economics of the publishing industry. His contribution to the Christmas market is Nelson Mandela's Conversations With Myself, which is doing respectably – though it is not quite up there with the work of Radio 2 DJs, TV tycoons and failed Australian pop stars.

How did we get here? He begins the story with the collapse of the net book agreement, which kept prices high and thereby held back the creation of a truly popular market, until 1997. "When that happened, the supermarkets came in with huge discounts, and you got a mass market. And what does a mass market want? They want what they get on radio, and TV, and in music, and film. So suddenly celebrities become the natural thing."

The watershed book, he reckons, was Billy, the biography of Billy Connolly by his wife – and Guardian columnist – Pamela Stephenson, which was published in 2001, sold more than a million, and thereby pointed the way. Down, on the whole: though the Connolly story was full of pathos, and capably written, what followed did not do great things for the culture. One thinks of, say, the four memoirs credited to Katie Price (she's already on to number five, apparently), Jason Donovan's Between The Lines, or Kerry Katona's landmark Too Much, Too Young: My Story of Love, Survival and Celebrity.

Last year, Geller tells me, was something of a celeb-publishing disaster, embodied by the underperformance of Ant and Dec's Ooh, What A Lovely Pair: Our Story (which did 330,000 in paperback, but failed to recoup a mind-boggling £2.8m advance). But 2010 is looking much better: with Jamie Oliver's 30 Minute Meals leading a high street publishing stimulus, and McIntyre, Sugar and the meerkat also doing their bit, the seasonal book market seems to have been miraculously revived, even as consumer confidence apparently plunges. That said, some of the numbers do not quite add up: McIntyre, Geller reminds me, received a reported £2.3m advance from the Penguin group, which means he'll have to sell in advance of 600,000 hardbacks if anyone's to make a profit. "There's no way he's going to do it, but that's still a successful book. It depends how you gauge success."

This last point goes straight to the book industry's strange business model, the fact that financial exactitude may be less important than keeping the whole machine ticking over.

"You buy turnover by having celebrities," says Geller. "You've got costs: distribution, employment, printers to keep happy . . . and if you've got something you know you're going to print at least 200,000 copies of, that keeps the machine running. You have to have turnover: if you don't, you're left with a small company. It's a self-fulfilling thing." To some ears, this may sound like the economics of the pre-internet music industry: sign a lot, pay whatever it takes, keep the fun going – and hope you luck out with at least one big hit a year.

But anyway: I have books to read. Having put down what I'm currently reading (Keith Richards's Life, which is great), I begin with Minogue's My Story, because she is the one contemporary celeb author I have met: at a west London branch of TGI Fridays circa 1997, when we fell into a weird and bitter argument about whether Robbie Williams should be blamed for losing himself in drink and drugs after exiting Take That. I sympathised with him; she, like a true show-must-go-on veteran of an Australian institution called Young Talent Time, did not – and it all got rather heated and shouty. Which is more than can be said for My Story, in which most of her anecdotes fall flat, like the kind of pub stories that are followed by pregnant silences.

She recalls watching a cast-member from Prisoner Cell Block H chainsmoking at an Aussie TV studio: "It's odd to think of it now," she says. Oh, it is! One paragraph from the end, she serves up this gripping picture of her current domestic bliss: "I wouldn't exactly say it's a quiet house . . . Kris [her other half] has bought a new 3D TV that looks as big as a cinema with surround sound that makes the house rock." To cap it all, there is this picture of her less-than-spectacular pop career circa 1989: "I seemed to be a mysterious, dark punk version of my older sister . . . it gave me more street cred." No it didn't!

There is much more: a boob job, nude shots for Playboy in which she was done up like Crocodile Dundee, and her valiant efforts to pretend Kylie's success has never been an issue: "The truth of the matter is that I never felt like I was competing with my sister. I'll say it again: I NEVER FELT LIKE I WAS COMPETING WITH KYLIE." So there you are.

After that, I do the Michael McIntyre book, which is a bit like having someone with a mild personality disorder shouting in your ear for six hours. He has an interesting story, of sorts: among the other strands of his pre-fame life, his father was a close associate of the anarchic DJ-turned-comic Kenny Everett, with whom his mum – some 17 years dad's junior – sated her appetite for the high life by regularly going clubbing. This all contributes to amusing enough stories, but there are insurmountable problems: a habit of digressing at ridiculous length; gags that don't work too well in bald print; and quite unbearable smugness. This is him, for example, on performing at the O2 arena: "Before my tour started, I saw Madonna there, the first night I did was replacing Michael Jackson, the night before my final gig Beyoncé was there. It simply doesn't get any bigger than this."

Over four days of mind-bending effort, I then tackle five more.

Chris Evans's Memoirs of a Fruitcake picks up where last year's It's Not What You Think left off: in 1997, when he borrowed £85m to buy Virgin Radio off Richard Branson, and commenced a long lost-it period that included his transformation into "a multi-millionaire part-time DJ", visits to hundreds of pubs, and his strange marriage to Billie Piper. It just about holds my attention, though I am left wondering how a book so defined by the getting and wasting of huge amounts of money will play in an age of fiscal grimness and belt-tightening. One chapter begins with a list titled "10 must haves when I built my dream house" and describes Evans being helicoptered around the stockbroker belt with a view to buying a new mansion, which I'm sure will resonate brilliantly in, say, Middlesbrough.

Still, at least it vaguely gets my blood rising – unlike Simon Pegg's distinctly un-gripping Nerd Do Well, in which he expends hundreds of pages on his memories of the 70s and 80s (you know the drill: Spangles, Star Wars, Princess Di haircuts, the usual), mysteriously fails to tell the reader anything much about Shaun of the Dead or Hot Fuzz, and decides to weave in a very odd, half-written story about a re-imagined version of himself and a "robotic butler". A talented and apparently nice fella, I'm sure, but his publishers have reportedly paid him £1m for three books, and so far, this one has done around 25,000 copies (insert Family Fortunes-esque "Uh-uhhhh!" noise).

After that, I have to speed up, for fear of madness. Cheryl Cole's Through My Eyes is a picture portfolio, peppered with laser-like insights ("the paparazzi can be really scary"), which can be satisfactorily dealt with in around 20 minutes. Russell Brand's Booky Wook 2 seems slight and widely spaced, and amounts to a breathless diary of his recent experiences – though there is a reasonably diverting chapter about what we must now call "Sachsgate" (when, he recalls, "the sky was black with scandal").

Paul O'Grady's The Devil's Ride Out centres on his often grim experience of the 70s, and has one unexpected advantage over most of the competition: on this evidence, he can actually write, with an understated grace and admirable sense of comic timing. Susan Boyle's The Woman I Was Born To Be, by contrast, is pretty much what I expect: an icky feast of anecdotes, homespun wisdom (eg "Memory is like a jukebox: push the right button . . . and you're transported straight back to a time and place") and truisms ("Being a postman is a full-time job") that seems to have been put together by someone called Imogen Parker. On the whole, it makes me feel unbearably sad: the dedication says simply "for my mother", which comes unexpectedly close to making me weep.

In other words, I have now taken a distinct turn for the worse – something conclusively proved by an afternoon in the company of Gok Wan's Through Thick and Thin. Just to make it clear: I have only ever watched How to Look Good Naked by accident, and the entire Gok phenomenon makes about as much sense to me as, say, Coldplay. But after 20 minutes, I cannot put it down.

The plotline is simple and affecting enough: raised by a Chinese father and English mother who ran restaurants in Leicester, he feasted on what he calls "deep-fried love", and ended up chronically overweight, and bullied. On the former score, he does not hold back: "My eyes were deep set and appeared piggy in the mass of fat on my face," he writes – a condition that led eventually to anorexia, described in the unsparing detail of food diaries ("Saturday 16 March: two teaspoons of honey, 40 laxatives"). Of course, everything eventually aligns correctly, and he becomes the successful if slightly irksome stylist-cum-unqualified psychiatrist we now know, but fair play to him: he probably deserves it.

And so to Alan Sugar. The thrillingly titled What You See Is What You Get is the best part of 600 pages long. Obviously, there is a story in there somewhere: how a wily Jewish kid from east London sussed out that the future would be defined by consumer electronics, and made a mint. But where to find it?

At one point, Sugar writes: "I could spend hours talking about every single amplifier and product we ever made, and it would be dead boring to everyone other than the old saddo hacks who used to work for me or buy from me." This lifts my spirits, slightly. But he follows it with this: "Stan Randall arranged the construction of the production line at Ridley Road and Mike Forsey got on with the design of the IC2000 [a hi-fi amplifier]. I did the mechanical drawing for the cabinet and chassis. This time, we moulded some very fancy silver knobs and slider controls. The front panel layout design of the product was down to me. I designed some flash aluminium toggle switches and the whole thing looked a real mug's eyeful. Moreover, it was a bloody good amplifier and it ticked all the boxes as far as the specification was concerned."

Who is this for? What is the point of it? The same exhaustive approach is applied to the mathematics of pricing, problems with "hard-disk controller cards", and just about everyone Sugar has ever employed ("the production line was being run by a no-nonsense fellow by the name of Dave Smith"). You would have to be out of your mind to persevere much past page 30. I have to, and that's roughly the state in which it leaves me.

Which brings us to the essential reason why the majority of modern Christmas bestsellers are so amazingly bad. Even if some of them have been ghostwritten, you often sense there has been precious little editing. No one – apart, in fairness, from Paul O'Grady – ever seems to deliver much context, or pause for thought, or indulge in any kind of reflection: better, it seems, to just go: "I was born ages ago and my mum and dad were nice but poor but then I got a lucky break and now I'm on TV and everything and here is a picture of me on our honeymoon in the Maldives."

Put simply, many of these books are deeply, desperately, profoundly infantile, and at my lowest point – roughly, at around page 300 of the Sugar memoir – I begin to suspect that a miserable formula is at work. It goes like this: get celeb, let them write whatever slipshod rubbish they fancy, and don't worry because 1) the more pages, the more people feel they're getting value for money; and 2) by Boxing Day, these books will already be either gathering dust, or on their way to the local Sue Ryder shop.

One other thing. The aforementioned meerkat book is titled A Simples Life, is credited to "Aleksandr Orlov" and contains the chilling inscription "this is an advertisement feature on behalf of comparethemarket.com", which essentially means the public are being asked to pay for an advert. It is an extremely cynical and thin work, based around a dependable enough trick: laughing at Johnny Foreigner. The prose, if you can call it that, features such gems as: "My home is a bit like English palace of Bucking Hams." If someone buys you it for Christmas, you should probably hit them with it.

My ordeal finally comes to a close on a Thursday afternoon, when in celebration of the end, I put in a call to the HQ of Waterstone's and speak to their head of PR, a book industry veteran named Jon Howells, who has been in the trade since 1991.

We talk for 20 minutes: he concurs with Jonny Geller's picture of the end of the net book agreement sending everything haywire, tells me that McIntyre may have stolen Peter Kay's comedy-book thunder, and mentions the promotional importance of TV chatshows. Most importantly, he suggests I stop thinking about all this stuff in the same context as what industry types call "range" – ie the books racked in the back of the shop – and realise what I'm dealing with.

"These books are a part of mainstream entertainment," he says. "Cheryl Cole has got a book out this Christmas, she's also got a new album out, and she's all over the telly. The book is one part of a general programme for somebody like that. You could make the same argument about Gok Wan, or Paul O'Grady. Or Michael McIntyre. It's all part of a brand. These are people with a huge amount of fans, and they want to buy product."

Has he read any of the big Christmas sellers? "I'm reading the Keith Richards book," he says. "I'm eking that one out, because it's brilliant. I've read some of the Russell Brand, which is good fun. I've read about half of the Stephen Fry book. I've got quite a few books on the go."

I reveal how I've spent the last couple of weeks, and mention them all: Minogue, McIntyre, Cole, Boyle, Evans, Pegg, O'Grady, Brand, Wan, Sugar and the meerkat.

"You've even done the meerkat," he marvels. "That's above and beyond the call of duty." A Simples Life, he tells me, took people such as him by surprise.

"How do you judge how well a book based on a fake animal in a car insurance ad is going to do?" he marvels, and then delivers his version of an inescapable truth about capitalism. As Paul Weller once sang, the public gets what the public wants – so maybe jumped-up pseuds like me should leave them to it.

"That book is doing well," he says. "People like it." He says the next bit with slightly less cheer. "Merry Christmas to them."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion