The past year has been a bumper one for the books world online. Literary blogs may have been around for a while, but 2010 was when word geeks around the world turned en masse to social media. Arguments were won or lost on Facebook over the use of the present tense and favourite fonts. The ideal daily word count for an aspiring novelist was hotly debated (anything between a modest 500 words and an alarming 8,000, apparently).

Tens of thousands of titles were championed and trashed. Margaret Atwood, AL Kennedy, Douglas Coupland, Alain de Botton, Hari Kunzru and Linda Grant all revealed themselves to be slaves to Twitter.

One of the year's most entertaining spats concerned the ubiquitious Jonathan Franzen and whether his novel Freedom was overrated. "There are other books. Don't dislike him per se. Disliked his response to being Oprah pick, overcoverage in Times, elsewhere," was novelist Jennifer Weiner's tart Twitter verdict. Jodi Picoult responded that the New York Times "favours white male authors" and soon the spat became news.

It was on Twitter, too, that news of the infamous theft of Jonathan Franzen's glasses was first reported, with a partygoer at the UK launch of Freedom tweeting: "Helicopter above Kensington Gardens, trying to find #Franzen glasses. Apparently miscreants jumped into Serpentine to escape."

Unlike some other social media sites, Twitter is fairly bullshit-proof, since it's mostly obvious who the person is and whether what they're saying is genuine. This makes it ideal for acerbic, often countercultural commentary – and for authors' spats. There are regular to-and-fro arguments about who has written the most number of words that day or who knows the most about the Google Books Settlement Agreement (a move to protect digital copyright).

Much online attention this year was given to the rumbling row about fake Amazon reviews. This kicked off in April when suggestions were made that historian Orlando Figes had libelled several rivals under an assumed name on Amazon (he initially denied the charge but eventually admitted it). Rachel Polonsky (one of his victims) was instrumental in exposing him; her Facebook friends had access to her thoughts on the matter long before they appeared in print.

Another scandal followed in June, when crime novelist Philip Kerr took his revenge on historian and book reviewer Allan Massie by posting his verdict of Massie's work on Amazon: "When I pay twenty quid for a 'nuanced' history of the Stuarts, I don't expect to be served up a slab of cheesy prose from a crappy old novelist." PD Smith, author of Doomsday Men (Penguin), tipped his Twitter followers off: "More revenge reviews: Kerr has a go at Massie."

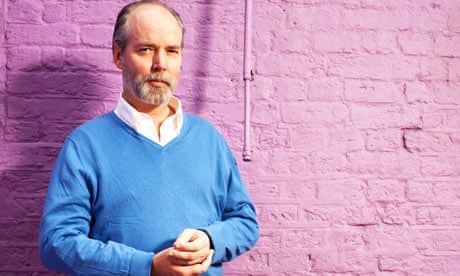

But it's when literary style comes under threat that the indignation really kicks off. Writers' feeds erupted in September when the former Booker judge Philip Hensher slammed three Booker-shortlisted novels (by Emma Donoghue, Tom McCarthy and Damon Galgut) as "weird" because of their use of the present tense.Philip Pullman agreed this was "a silly affectation".

Linda Grant wrote on Facebook: "Thank God someone has said this. I could not agree more. The lure of immediacy sinks into ever-present cliche." But Hari Kunzru thought the opposite: "Completely disagree w Pullman, Hensher on present tense. Present avoids lapidary fx of past, useful temporal slides." (Eh?)

The most common literary use for social media sites, as for blogs, remains reading tips. "I love book recommendations from Twitter," says Elizabeth McCracken, keen tweeter and author of An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination. "I often hear books news there first. Her two top social media-influenced reads of 2010 were: Skippy Dies by Paul Murray (Hamish Hamilton) and Slut Lullabies by Gina Frangello (Emergency Press), described as "the lovechild of Mary Gaitskill and Philip Roth". Novelist Jojo Moyes, meanwhile, says she discovered Our Spoons Came from Woolworths by Barbara Comyns (Virago) and The Group by Mary McCarthy (Virago) on Twitter.

But she sounds a note of caution. "It's been a huge disappointment to unfollow a couple of literary heroes who were just unutterably smug or self-promoting." (Unfortunately, she won't name names.) "If you supposedly love words, then using social media for constant self-promotion rather misses the point." Sound advice. Authors everywhere know their new year's resolution, then. Carry on tweeting and Facebooking, but please, about others' books, not just your own.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion