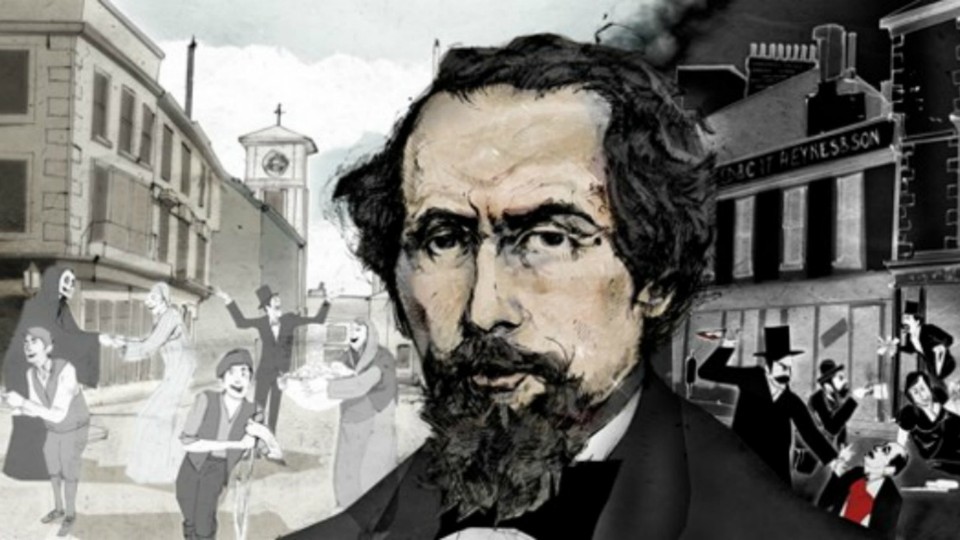

The Dark Side of Dickens

Why Charles Dickens was among the best of writers and the worst of men

If offered the onetime chance to travel back into the world of the 19th-century English novel, I once heard myself saying, I would brush past Messrs. Dickens and Thackeray for the opportunity to hold speech with George Eliot. I would of course be wanting to press Mary Ann Evans on her theological capacities and her labor in translating the liberal German philosophers, as well as on her near-Shakespearean gift for divining the wellsprings of human motivation. When compared to that vista of the soul and the intellect, why trouble even with the creator of Rebecca Sharp, let alone with the man who left us the mawkish figures of Smike and Oliver and Little Nell, to say nothing of the grisly inheritance that is the modern version of Christmas? Putting it even more high-mindedly, ought one not to prefer an author like Eliot, who really did give her whole enormous mind to religious and social and colonial questions, over a vain actor-manager type who used pathetic victims as tear-jerking raw material, and who actually detested the real subjects of High Victorian power and hypocrisy when they were luckless enough to dwell overseas?

I can still think in this way if I choose, but I know I am protesting too much. The first real test is that of spending a long and arduous evening in the alehouses and outer purlieus of London, and here it has to be in the company of Dickens and nobody else. The second real test is that of passing the same evening in company with the possessor of an anarchic sense of humor: this yields the same result. What did oyster shuckers do, Dickens demanded to know, when the succulent bivalves were out of season?

Do they commit suicide in despair, or wrench open tight drawers and cupboards and hermetically-sealed bottles—for practice? Perhaps they are dentists out of the oyster season? Who knows?

This pearl was contained in a private letter not intended for publication (Dickens was almost always “on”) and is somewhat more searching than the dull question—“Where do the ducks in Central Park go in winter?”—that was asked by the boy who spoke so scornfully of “all that David Copperfield kind of crap.”

It would be understating matters to say that Thackeray rather looked down on Dickens, but, even as Vanity Fair was first being serialized in 1847, he picked up the fifth installment of Dombey and Son and then brought it down with a smack on the table, exclaiming the while, “There’s no writing against such power as this—one has no chance! Read that chapter describing young Paul’s death: it is unsurpassed—it is stupendous!”

Almost a decade later, Dickens was dispatching an admiring note to George Eliot on the publication of her very first fiction, Scenes of Clerical Life. He felt he had penetrated the guileless disguise of her nom de plume: “If [the sketches] originated with no woman, I believe that no man ever before had the art of making himself, mentally, so like a woman, since the world began.”

So I find the plan of my original enterprise falling away from me; I must give it up; there is something formidable about Dickens that may not be gainsaid.

He may not have had Shakespeare’s or Eliot’s near omniscience about human character, but he did say, in an address on the anniversary of the Bard’s birthday: “We meet on this day to celebrate the birthday of a vast army of living men and women who will live for ever with an actuality greater than that of the men and women whose external forms we see around us.” As Peter Ackroyd commented in his Dickens (1990), he must have been “thinking here of Hamlet and Lear, of Macbeth and Prospero, but is it not also true” that in Portsmouth in February 1812 were born “Pecksniff and Scrooge, Oliver Twist and Sairey Gamp, Samuel Pickwick and Nicholas Nickleby … the Artful Dodger and Wackford Squeers …?” I cite this occasion for a reason. In Michael Slater’s volume, we learn only that on April 22, 1854, Dickens chaired “a Garrick Club dinner to celebrate Shakespeare’s birthday.” This is of course worth knowing in its own right, but is perhaps a little bloodless by comparison. Slater is invariably flattering toward Ackroyd’s work, but could perhaps have taken a leaf or two from its emotional eloquence.

Who does not know of the formative moments in the life of Dickens the boy? The feeble male parent, the death of a sibling, the awful indenture to “the blacking factory,” the pseudo-respectable school where the master slashed the boys with a cane as if to satisfy what was later identified in Mr. Creakle as “a craving appetite.” The sending of the father to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison, the refuge taken by a quakingly sensitive child in the consoling pages of fiction … all this we have long understood. So great was the dependence of Dickens on his own life experience that he almost resented the fact and was very guarded, even with his loyal biographer, John Forster, on the question, as if unwilling to admit such a (very non-Shakespearean) limitation. This is why it is so good to have the “autobiographical fragment” that Forster preserved and later published, which formed a sort of posthumous codicil to David Copperfield and still helps explain why that novel above all others was its author’s favorite. Forster diagnosed in his subject a syndrome of “the attraction of repulsion,” which, while simple enough in its way, goes far to explain why Dickens was at his best when evoking childhood misery, incarceration, premature mortality, hard labor, cheating and exploitation by lawyers and doctors, and the other phenomena that were the shades of his own early prison house. With these, as we now slackly say, he could “identify.”

If valid, this analysis would also go some distance to explain the very severe constraints on Dickens’s legendary compassion. This is the man who had a poor woman arrested for using filthy language in the street; who essentially recast his friend Thomas Carlyle’s pessimistic version of the French Revolution in fictional form in A Tale of Two Cities (Slater is especially good on this); who dreaded the mob more than he disliked the Gradgrinds. It would also account for his weakest and most contrived novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, and its companion nonfiction compilation, American Notes. Genuine radicals and reformers in mid-19th-century England were to be defined above all as sympathizers with the American Revolution and with the cause of the Union in the Civil War. Dickens was scornful of the first and hostile to the second. His exiguous chapter on slavery in American Notes was lazily annexed word-for-word from a famous abolitionist pamphlet of the day, and employed chiefly to discredit the whole American idea. But when it came to a fight on the question, he was on balance sympathetic to the Confederate states, which he had never visited, and made remarks about Negroes that might have shocked even the pathologically racist Carlyle. I had not understood, before Slater’s explanation, that the full title, American Notes for General Circulation, was a laborious pun on the supposed bankruptcy of the whole “currency” of the United States. Karl Marx, that great supporter of Lincoln and the Union, was therefore probably lapsing into a rare sentimentality when he wrote to Friedrich Engels that Dickens had “issued to the world more political and social truths than have been uttered by all the professional politicians, publicists and moralists put together.” (Ackroyd mentions this letter, while Slater does not.)

Ackroyd, I find, is also more clear-eyed when it comes to Dickens and the Victorian empire. It’s easy to tell, from the protractedly unfunny sarcasm about Mrs. Jellyby and the mock-African hellhole of Borrioboola-Gha in Bleak House, that the author did not possess the gift of imaginative sympathy when it came to those outside his immediate ken, or should I say kin.

But what is to excuse Dickens’s writing to Angela Burdett-Coutts, about the 1857 Indian rebellion, that if he had the power, he would use all “merciful swiftness of execution to exterminate [these people from] the face of the Earth”? Slater allows this an attenuated sentence, while Ackroyd quotes a fuller and even fouler version of the same letter, adding, “It is not often that a great novelist recommends genocide.” Nor will it do to say that such attitudes were common in that period: when Governor Eyre put down a revolt in Jamaica with appalling cruelty in 1865, it was Dickens and Carlyle who warmly applauded his sadism, while John Stuart Mill and Thomas Huxley demanded that Eyre be brought before Parliament. Once again, Ackroyd emphasizes this while Slater speeds rapidly past it.

Finally, is there not something a trifle sinister in Dickens’s letter to Lord Normanby (such a name of lofty entitlement, he himself would have been hard put to invent), written while he was struggling to finish The Old Curiosity Shop, offering to go to Australia on behalf of the British government and there to write a properly cautionary account of the hellish conditions in Her Majesty’s penal colonies? He had worried that the deterrent effect of this horrible system had been diluted, with too many stories in circulation of ex-convicts making fortunes. Old Magwitch, evidently, should not have been let off so easily … (One of Dickens’s ostensible purposes in visiting America was to study its prisons, yet Slater tells us there is no evidence that he ever troubled to read de Tocqueville, who had formed and carried out the same intention in rather superior form. But what we want to understand is whether Dickens engaged in any vicarious gloating, on this and other “attraction-repulsion” forays into the lower depths.)

What is necessary, therefore, is a portrait that supplies for us what Dickens so generously served up to his hungry readers: some real villainy and cruelty to set against the angelic and the innocent. Yet somehow the same tale continues to write itself. We “know” the bewitching figure so well that speculations are possible about his suffering from obsessive-compulsive disorder and versions of the bipolar. Claire Tomalin has etched in for us the long-absent figure in the frame, Ellen Ternan, who was plainly the consolation of Dickens’s distraught sexual life. We are aware that the great prose-poet of childhood was acutely conscious of having failed his own offspring. Yet we remain in much the same position as those naive Victorian readers who were so upset when John Forster told them that the respectable old entertainer was a man who had drawn his dramatis personae from wretched life itself. Always saying that he sought rest, and always exhausting himself, he may have been half in love with easeful death. The next biography should take this stark chiaroscuro as its starting point.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.