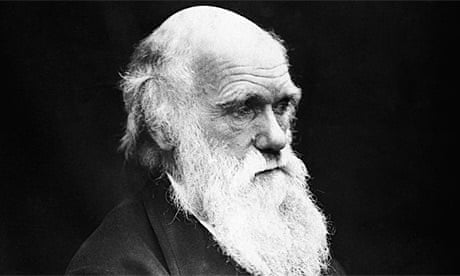

Like a one-man tribute band, Steve Jones plays Darwin's greatest hits. Unlike most tribute bands, he delivers a surer performance than the original. He is a more natural raconteur than Darwin and he knows a great deal more about Darwinian descent with modification.

Neither statement reflects on Darwin's greatness. The first is simply an observation about contemporary taste, and the second is a reminder of the nature of science, which builds upon, overtakes and redirects even the greatest achievements of the past. But Almost Like a Whale is a tribute, all the same: Jones uses the same chapter titles as On the Origin of Species, follows the same sequence of themes, and punctuates his own improvisations with telltale riffs and licks sampled from the master.

The performance is so elegantly composed, so deftly performed and so consummately timed that, at various points it is possible to confuse Jones with Darwin himself, who indeed is quoted both directly and openly, and subtly and without warning, in every chapter. Anyone who embarks on this book is in danger of double vision: I began reading it by itself, but soon had the Origin open for cross reference at parallel chapters, so fascinated had I become in the ways that the style of the very unVictorian Jones would modulate itself to incorporate graceful lines directly from Darwin.

When the book first appeared in 1999, it was warmly welcomed, although at least one critic wondered why Jones lumbered himself with the scaffolding first erected by Darwin: why didn't he give us the full Jones-alone version of evolutionary thinking? I thought he already had, if indirectly, in books before and since. The value of choosing the Origin as a roadmap is that Jones could stick to Darwin's story but at the same time begin to discuss in the light of 20th century scholarship all those things Darwin could not have known, or felt troubled by.

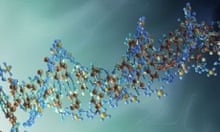

Roughly 100 years after the publication of Origin, two complete, unexpected and once-unimaginable scientific revolutions independently reinforced the brilliance of Darwin's insights. One of them is the revolution in genetics delivered by the identification of the double helix of DNA. The other is confirmation of a dynamic Earth, complete with oceans that open and close, mountains that grow and collapse, and continents, "great arks of rock that wander the globe and, now and again, collide."

The first of these provides the machinery Darwin could not have known about, nor even guess at, for the tiny changes upon which natural selection would act. The second could account for so much of the unexplained biogeography of evolution that puzzled the great man and his peers.

But, besides completely new science, there is now a huge body of confirmatory evidence painstakingly won from the older sciences of palaeontology, geology, botany, zoology, oceanography, anthropology, microbiology, epidemiology and medicine, all of which were directly stimulated by Darwin's theories: the sage of Down House gave the natural scientists a set of precise questions, and new answers began to emerge everywhere. So, there is a lot to be said for an attempt to update and annotate the first sacred text of evolutionary biology.

But there is a second reason, one that quietly insists on its own validity all the way through this book. To the Creationists, Darwin is the great Satan. They do not feel that they have to prove that Steve Jones, Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Dawkins and Edward O Wilson are wrong, or Haldane, Huxley and a hundred other natural historians. All they have to do is demonstrate that Darwin is unproven, or fundamentally flawed, or that he had delivered "only a theory". That is why so many of them keep producing arguments that Darwin, with the evidence available to him at the time, could not satisfactorily address. Almost Like a Whale addresses them, and it does so with a cool assurance that should persuade the open-minded, and thrill the already converted.

The latter, of course, will read it for the headlong pleasure of the accumulated biological intricacies and subtleties and unresolved questions that exist within the confirmation of Darwin's great idea; and for the clever parallels within the exposition of the human-imposed notion of species and variety (what, for example, is a German? Who fits the 1913 definition of "German blood?" Before 1870, were the Rhinelanders German?)

This is a subject that can choose its instances and analogies from all history and geography, and marvels appear on almost every page. The humpback whale can carry 1,000 lbs of barnacles: to challenge these tiny parasites its skin grows at a rate 300 times faster than human hide. Poppies can leave 30,000 seeds in a square yard of soil: of course they began to bloom when grazing stopped and the Flanders Fields were cultivated by swords, shells and blood after 1914. A bomb that hit the Natural History Museum caused a fire that was quelled by hoses and in the warmth and the flood a mimosa seed collected in China in 1713 germinated and began to flower: a strange awakening that illustrates life's tenacity, and at the same time its fragility.

Jones is terrific, too, on the geological record and its caprices. The rocks have yielded 165 species of extinct elephant; only two species roam the planet today. Nine billion passenger pigeons once blackened the skies of America; the last perished in 1914, but fossil evidence for the creature's existence has never been found. Without a written record, no one now would ever know it had been there.

Throughout, where possible, Jones glosses, expands or enriches Darwin's themes using Darwin's examples – pigeons, dogs, farm creatures, bees, Galápagos finches – but with fresh observation and research. The whole story is told with the focus, energy and occasional droll asides that might be the Jones trademark.

I wanted to hear just a little more about his own youthful collecting mania (cheese labels?) and my favourite of many throwaway Jones lines, involving the life cycle of the sea squirt that "after an active life, settles on the sea floor and, like a professor given tenure, absorbs its brain."

I began by suggesting that Jones's tribute is in some ways more far-reaching than Darwin's Origin, and with a better view of its subject: but that too is less treasonable than it might sound. Not only does Jones stand, to play with Newton's metaphor, on a giant's shoulders; the real reward of this book is to remind us, once again, what a colossus Charles Darwin really was.

Tim Radford's geographical reflection, The Address Book: Our Place in the Scheme of Things was published by Fourth Estate on 28 April

July's Science Book Club choice

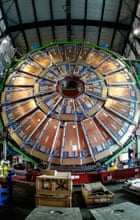

In 1993 Steven Weinberg put the case for an American particle accelerator that would never be completed, to answer questions about the ultimate nature of matter and energy that might instead be resolved in a tunnel under Geneva. Tim will review Dreams of a Final Theory on Friday 8 July

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion