How to Choose '25 Books That Shaped America'

A conversation with literature professor Thomas C. Foster about how he selected the titles in his latest book

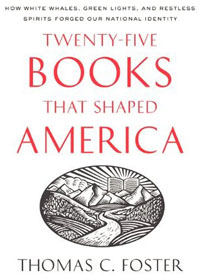

Harper Collins

Narrowing down more than two centuries of American literature to a list of 25 influential books is daunting. Do you include Hemingway or Fitzgerald? Huckleberry Finn or Tom Sawyer? And how do you determine what makes a book influential in the first place? This was the task University of Michigan literature professor Thomas C. Foster took on when he wrote Twenty-Five Books That Shaped America, which comes out today. In an interview with The Atlantic, Foster described how he made his list—and pondered whether changes in reading habits could affect the role of books in American culture.

What was your methodology for picking the 25 books on your list?

You're giving me credit for having a method—that's probably more than I deserve. When we first started talking about this project, I thought, "How in the world am I going to limit this? Where am I going to take it?" Part of the problem was solved by Jay Parini, who, right around the time we signed the contract and I sat down to get going brought out Promised Land: Thirteen Books That Changed America. And my first thought was, "I'm in trouble now." And my second thought was, after I'd looked through the table of contents and what he was doing, "This is great because he's done a bunch of things I didn't want to have to deal with."

His book is primarily about nonfiction works including How to Win Friends and Influence People, which I had no interest in doing. And I thought, "That's been done. I'm off the hook."

Parini also uses the phrase "changed America" rather than "shaped America," which is what you use.

I wanted "shaped" because I thought "shaped" opened up some possibilities. But it also meant they didn't have to be books where you could say, "This law got enacted because of this book. "

What else did you consider when you were making the list?

I wanted a representative sampling: Quite a lot of books from the 19th century, quite a lot of books from the 20th century. I wanted to have various groups represented. I didn't say, "I want one from column A, I want one from column B," but I wanted books that would look at the Midwest experience, some Eastern experience, various takes on race and ethnicity.

Then what?

I started coming up with a list. I wasn't sure how I could get down to 25, but I could get up to 50 or 60 pretty quickly. And then I started culling. It was more a matter of justifying the books I was staying with than it was asking the books to meet a standard. I assumed there was a standard—I just hadn't articulated it for myself.

I was very careful—and I think I addressed this several times in the book—I was very careful to avoid the definite article in the title. Because these are 25 books. These are not the 25 books that shaped America. There's a big difference there. They're exemplary rather than exclusive, I think. And that's how I intended them to be.

How did you cut the list from 50 or 60 down to 25?

I went with books that I had a fairly strong feeling about—mostly positive. I make an exception for The Last of the Mohicans, for which I was grinding my teeth. I'm with Twain on the subject of [James Fenimore] Cooper's prose. At the same time, he can make you turn pages in a way that any contemporary thriller writer would be happy to be able to do. Cooper's sort of a mix blessing where I'm concerned. I know a lot of people liked him rather better than I do.

Were there any books you wanted to include but didn't?

I tried and repeatedly failed to color outside the lines a little bit. I wanted to do The House of the Seven Gables, but it just didn't work out. So I wound up with The Scarlet Letter.

I get into AP English classes on a fairly regular basis, and there was a class over in East Kentwood, right by Grand Rapids, and I said, "Ok, I'm going to do this book on 25 American books—what should I include?" And I got the usual smattering of answers—everything from Gatsby to Ayn Rand to Chuck Palahniuk. But the title I heard almost universally from them was The Scarlet Letter. And I thought, "Well, you know there's something that works there for them." It wasn't that I didn't want to include it, it's just that I thought Seven Gables would take me in a different direction.

I did the same thing with Huckleberry Finn. I wanted to go with Tom Sawyer because the white-washing of the fence and Injun Joe and all that stuff—that's what people think they remember about Twain. And none of that is in Huck Finn. But you just can't not do Huck Finn. So I did Huck Finn.

Amazon

Which books are people going to complain aren't on the list?

There are two that spring instantly to mind: One is Catcher in the Rye, and the other is Red Badge of Courage. I may be wrong, it may be something else. I thought of Roots, I thought of Native Son, which I do address [in the conclusion]. It could be one of the McMurtry books—it could be Lonesome Dove. I doubt that. I think Catcher and Red Badge are where I'll catch the most flak. And that's OK. I want a conversation. I want people to engage the book. And part of that is, I suppose, to annoy them by not having everything that they might expect.

Your list assumes that books do have a role in shaping American society. One hundred years from now do you think a similar list will be made? Or will some other medium take over in influencing our culture?

First of all, I have to utter a disclaimer here, that I am an old-fashioned person. I teach English and American literature, and I do it primarily out of codex books. The codex itself probably won't be here in 100 years, or it won't be as common. We'll be reading electronically. I own a Nook—I own an electronic reader—and I read both forms. I don't know if I've figured out what the difference is.

Leaving that alone, I believe in books. I believe that they leave an impression that, for instance, a television show or a blog won't be likely to do. And to that extent, I think they probably will be around, whatever form they're taking. And the form will probably have changed into something that Gutenberg wouldn't have recognized.

But there will be something, and it will probably be prose or poetry in length, and it will have some kind of impact on us. Because we can engage for a longer time with a novel. You know, a film takes a couple of hours. Even if you're a fairly fast reader—and I'm not—a novel's going to take six or eight or 10 or 12 hours. You live with those characters, you live with that language a great deal longer even than you do with a film, which is our longest non-book medium. I think there will always be a place—I hope there will always be a place—for books, and not just old ones.

How does a list like this help endorse reading as a worthwhile activity?

I think it does a couple of things. One is that it asks people to go back to the books or in many cases to the books for the first time. And not take the received wisdom of what they may have heard about the books, or what they remember from high school, and actually look at them.

Were there any books in particular that you revisited in the process of writing this?

I went back to Moby Dick at the behest of my editor. I turned in an original manuscript that did not include that chapter. it actually included a chapter on Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Oh, interesting.

I had my reasons. But I got this email, and the subject line was, "The Wizard or the Whale?" I knew I'd been naughty when I turned it in, but I thought, "Well, I'm not sure I have much to say there." In a matter of something under two weeks, I reread Moby Dick and wrote the chapter because we were frantically trying to meet deadlines at that point. And I just found the novel so much better than I'd remembered it from when I was 19 or 20. So much funnier—but also so much more insightful about human relationships and ethnic diversity—my goodness, what a diverse place that ship is.

I was just fascinated by that work and what it had to say to me that it hadn't said to me 40 years ago almost.I was really taken with that. I hope people will have that experience.

The other thing I hope they'll realize is that this writing is part of a system or a continuum. When we're in school we often don't get that. We move from this work to this work to this work, and, yeah, we're told that they're all American literature or they're all English literature. My earlier books try to suggest that the whole of literature is a functioning system that can be studied—you can see how works speak to each other, and you can hear echoes and they use similar kinds of figurative codings. This one is about American literature—Shakespeare comes in, the Bible comes in, all kinds of things that aren't American. But there's a conversation or an ongoing dialogue in American literature where works are speaking to works.

Sometimes it's really overt. If you read all of John Updike—I don't know if anyone has done that—but if you read all of Updike, you're going to get a lot of Hawthorne. He runs back through particularly The Scarlet Letter several times. John Gardner, his book October Light is really The House of the Seven Gables in a lot of ways—updated, changed surely, but there are a lot of similarities.

Why do writers go back to these things? What are these kinds of experiences of their reading that bring that forward into their writing? When Hemingway says that all of American literature grows out of a book called The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, he's exaggerating just a little bit, but he's really talking about the way that Twain is our Dante. He frees writers up to write in the vernacular, which of course before Dante they didn't do. If you read Cooper or you read [Washington] Irving or you read any of the people pre-Twain, they're not writing in the every day language that Twain is writing in Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. I can imagine Twain laughing at being compared to Dante, but I'm going to stick with it here.