The Hidden World of the Typewriter

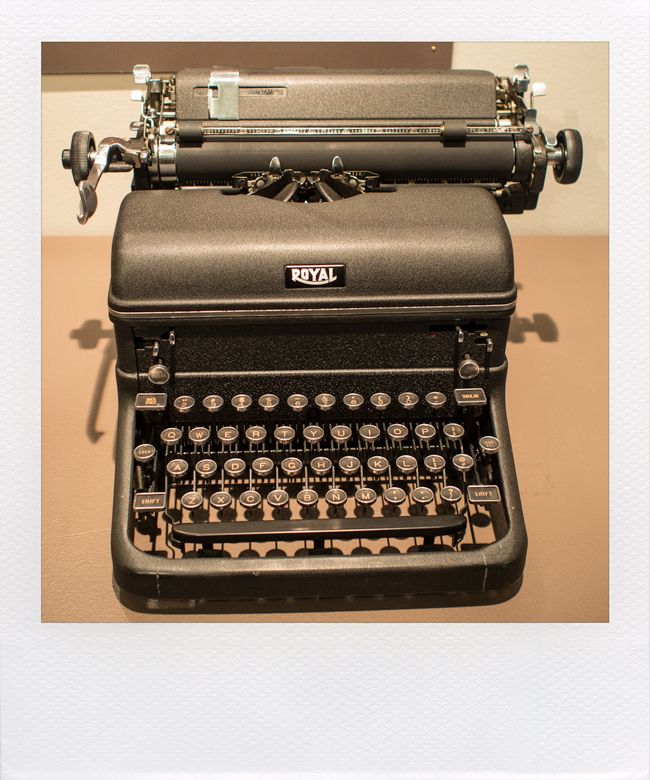

Before laptops and tablets came along, writers did their writing on clunky, unwieldy machines -- aids to work that were also works of art.

The typewriter is, among things, an archetype of today’s computers. But while computers are increasingly products of our disposable consumer culture – assumed and built to be upgraded often – typewriters were built to last. While occasionally some innovation or another would pop up – a machine made noiseless or self-correcting or electric – the general idea remained the same. Fingers mashed down a key, the key drove a lever with the designated character on it toward an ink-saturated ribbon, and with a decisive clack the intended mark was made (provided the typist’s fingers were accurate). It was a physical interpretation of intention-meets-action, thought-meets-paper, and many users maintained an ongoing relationship with their typewriters for years.

So intense was this relationship between writers and their machines, in fact, that many people who made their careers out of writing never made the transition to computers; Hunter S. Thompson used a typewriter until his until his death in 2005. And Cormac McCarthy is still click-clacking away, after selling his Lettera 32, which he’d been writing on for close to 50 years, at a charity auction a few years back for $254,500 – and promptly receiving another of the same model from a friend for $20. It's unsurprising that he'd stay committed to the heavy, clunky producer of words. Computers and other digital tools may have brought ease to writing; they don't offer, however, the deliberation that typewriters do -- the forethought required to avoid the particular punishment of a typer: a piece of correction ribbon or dab of White Out be required to eradicate an erroneous mark or misplaced musing.

There was a time that nearly every home and office had at least one typewriter, ready to tap out letters or lists, invoices or inspirations. Today, of course, the machines have gone the way of vinyl records, romanticized analog nostalgia, a sometimes-useful kitschy artifact with which to wax nostalgic. But, also like vinyl records, typewriters have their enthusiasts, cult followers and collectors drawn to their character and to the mystery of all the ideas and dreams that have been poured, or, rather, pounded, into them. Actor Tom Hanks is a collector, with a rumored 200 or more.

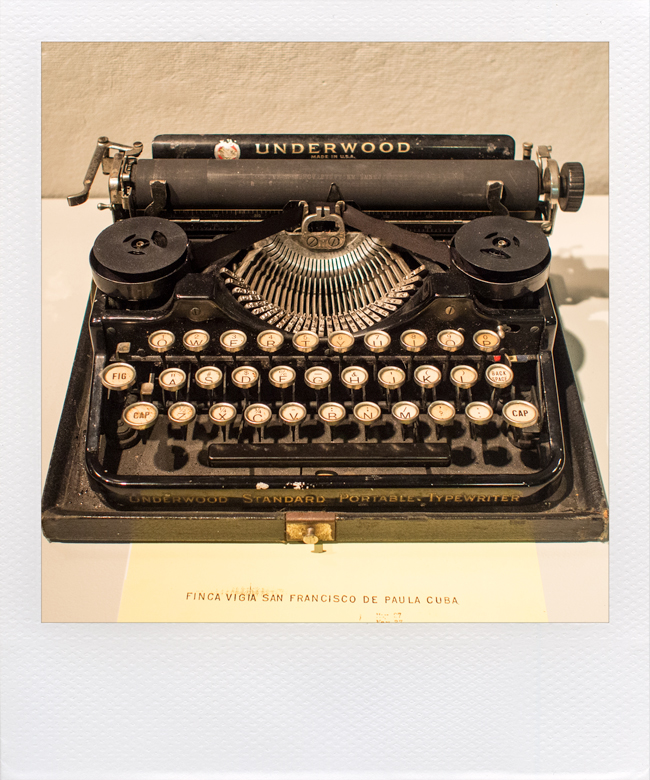

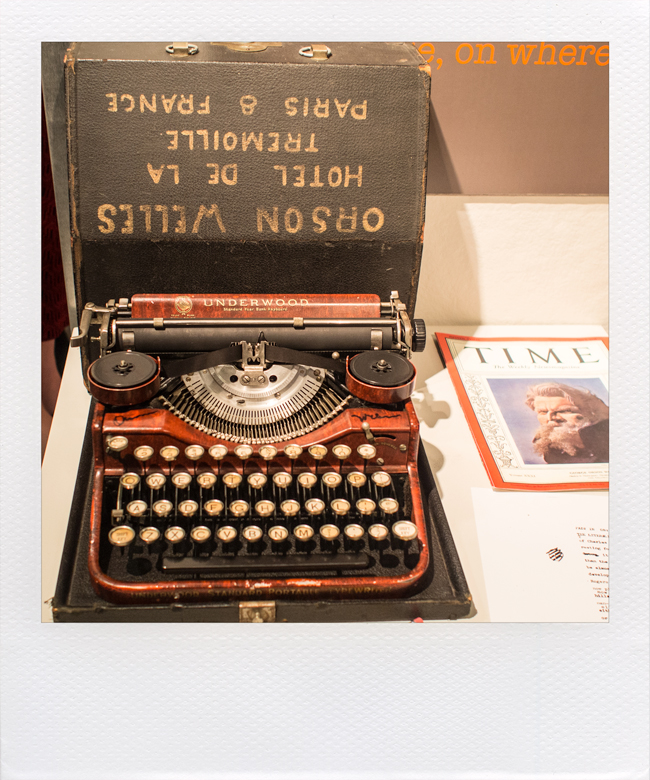

Ernest Hemingway, 1929 Underwood Standard: Hemingway once told Ava Gardner that the only psychologist he would ever open up to was his typewriter. (James Joiner)

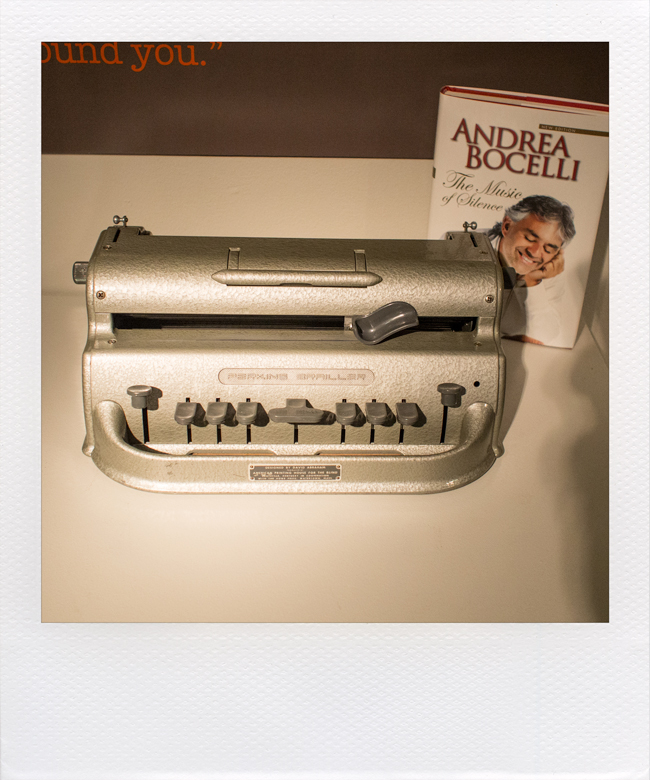

Andrea Bocelli, Standard Perkins Brailler: Blind since childhood, Italian tenor Maestro Andrea Bocelli used this Standard Perkins Brailler in his studies, and for opera verse from his memoir The Music of Silence. (James Joiner)

There’s one man, however, who has made it his life’s work to collect not just typewriters, but specifically famous people’s typewriters.

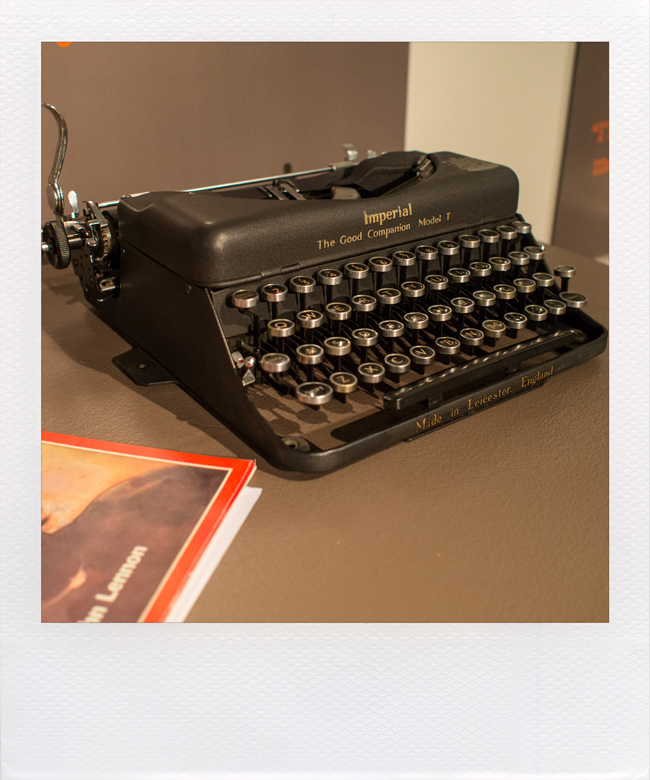

Steve Soboroff is a California businessman, with a career that includes running for mayor of Los Angeles, a brief stint as vice chairman of the L.A. Dodgers and a current appointment as one of the LAPD’s police commissioners. He is also the foremost collector of famous folks' typewriters, with a cache that spans the famous – John Lennon and Joe DiMaggio – to the infamous: He owns one of two units taken by the FBI from Ted Kaczynski’s Montana cabin.

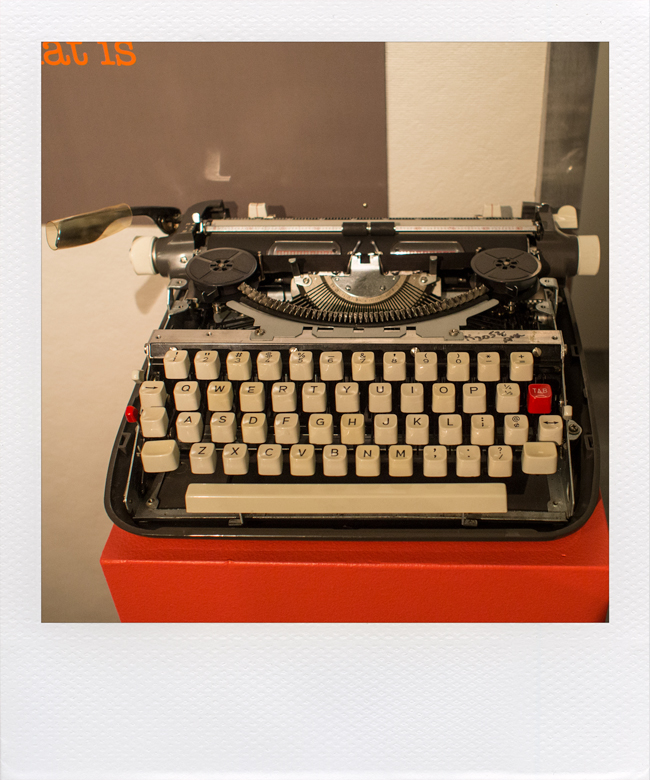

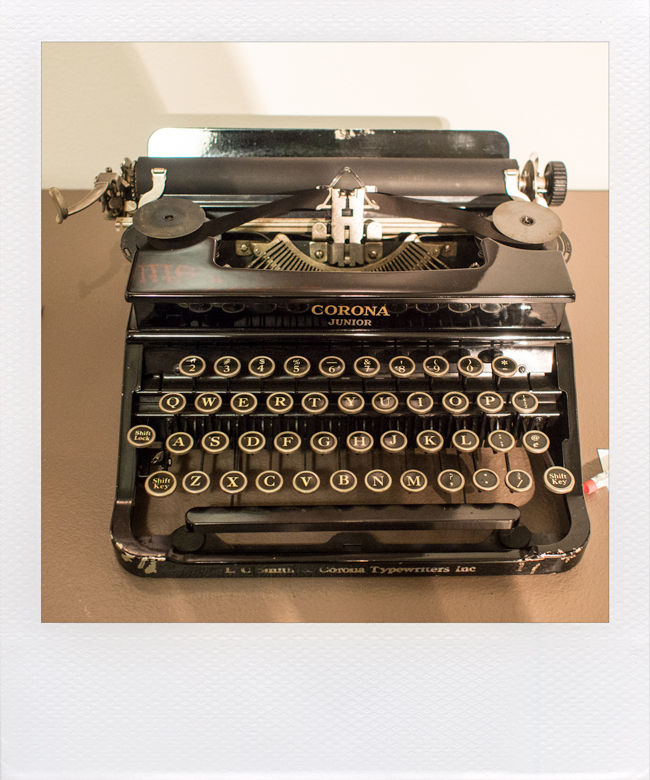

I met Soboroff in Boston, where a curated selection of his typewriters is being displayed at Northeastern University. The collection routinely tours, and people can type on their favorite luminary’s machine for a fee that goes towards a fund for journalism scholarships. I brought my camera; the images included here were shot, in keeping with the analog theme, on Impossible Project film for old Polaroid Cameras.

Soboroff and I are standing in front of a slightly haggard yet modern-looking model, and it’s conspicuously missing its cover. Soboroff is telling me about a letter exchange he’d had with the previous owner, the aforementioned Unabomber.

“The letter I wrote to him was, ‘Where is the cover to the typewriter?’ Now, I know. He made a bomb out of it.” Soboroff speaks loudly, gesturing to the small crowd of students who form a rapt audience. “I wrote it to him on this typewriter, I wanted to trigger him to respond to me …. So he wrote to me, it says, ‘I don’t return any letters, but today I received a letter that may make me change my mind. If you are who I think you are, then of course I’ll do my best to answer.’ So I thought, ‘well, huh. I ran for mayor of LA, maybe the guy knows who I am.’ My son said, ‘Dad, that’s not what he’s thinking. He’s thinking you’re your cousin.’”

Soboroff snorts.

“Well, I have a cousin named Jeffery Soboroff who I’ve never met, who was arrested for threatening to poison the water supply in a town in Iowa. I betcha he thinks I’m that guy.” He laughs, mimicking Kaczynski, “'Hey, I’m a mass killer, you’re a mass killer, we’re bros!’ Anyway, a month later I get a postcard from him: ‘It turns out you are not who I thought you were. Tough luck.’ Tough luck? Who’s serving 300 years in prison? I live in Malibu!”

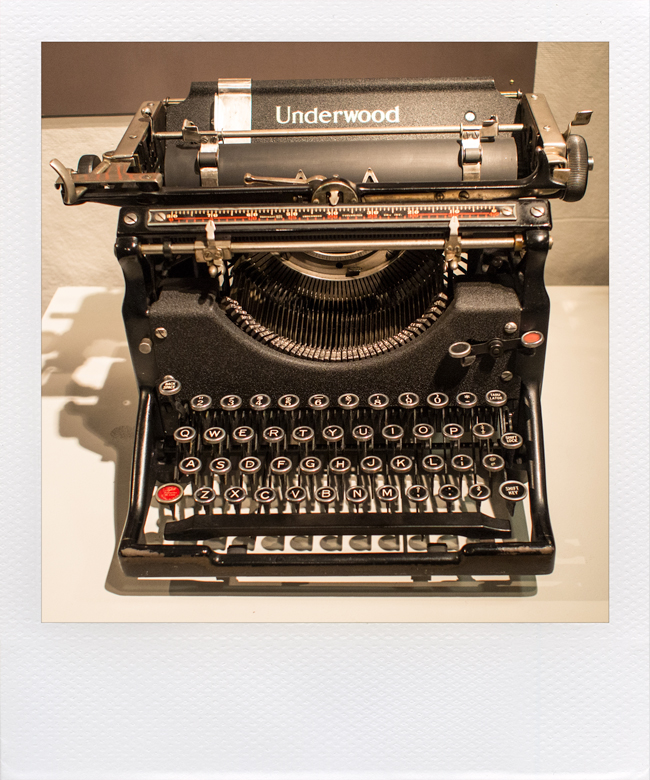

Soboroff has made national news with his passion project, most notably for his last-minute, Hail Mary approach to scoring one of 60 Minutes personality Andy Rooney’s treasured Underwood typewriters, which he did by contacting a random real estate broker – and ex-CIA operative - who just so happened to live three doors down from where the auction was happening. Long story short, he pulled it off, paying $3,000 -- only to receive a call from CBS’s lawyers fifteen minutes later offering him $125,000.

He declined.

Typewriters, after all, are much more than mere machines. Because they were such static items in a household -- furniture-like even in their writerliness -- things often got misplaced between the bottom of their case,s on which the bodies usually rested, and the typewriters themselves.

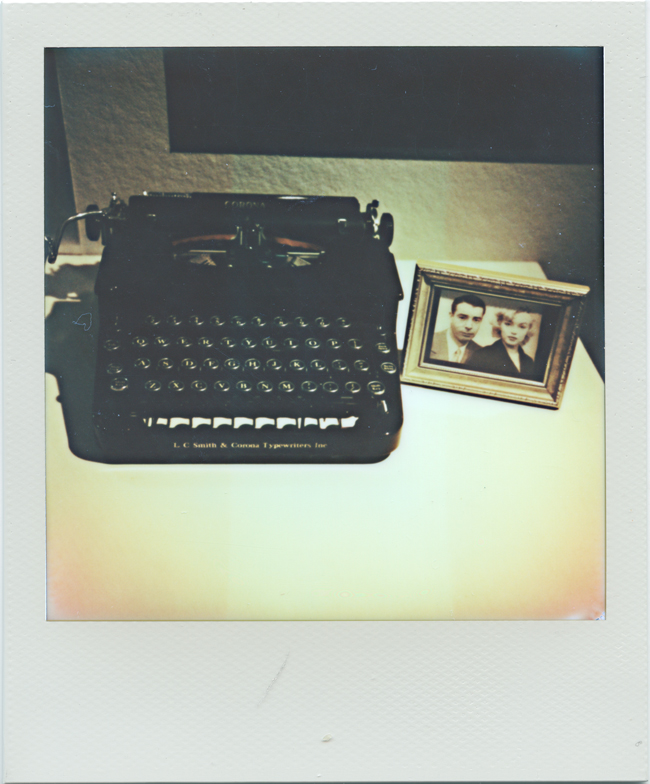

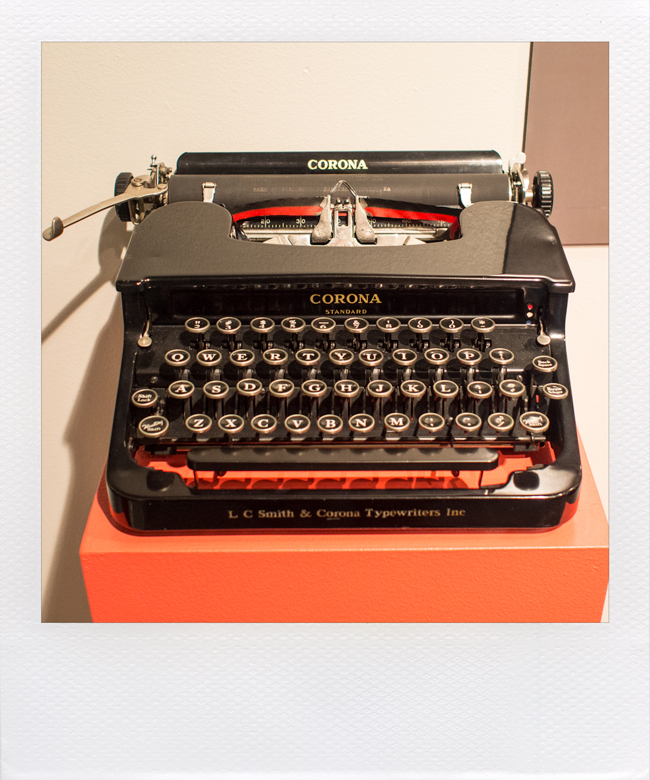

“This is the typewriter that Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe used in their home in San Francisco,” Soboroff says, gesturing toward a small, Art Deco-looking Smith Corona. “And underneath, in the box, was Joe DiMaggio’s credit card, cut up into little pieces. He probably didn’t want his wife to use it. I think she was a big spender! You never know what you’re gonna find.”

Soboroff also discovered, when cleaning out Hemingway’s Underwood, three old photo negatives.

“They were all crumpled up, and when I went to pick them up in my hand, they turned to dust. So I took a spatula and picked them up and took them over to a film lab in L.A. and asked them if they could do anything. So they steamed them, they shined a light through them, and they made one print of each. I forwarded them to the number-one Hemingway scholar in the world, a woman who works at Penn State University. Three minutes later she calls, so excited. She goes, ‘This is a photograph of his father, this is Ernest Hemingway, it's 1902. This is their summer home in Michigan.’”

Soboroff shrugs. “So that’s the kind of stuff … you know, I don’t know what this is worth, 'cause it’s priceless. There’s only one print of each.”

He chuckles. “And to think I almost forgot them in the cab!”

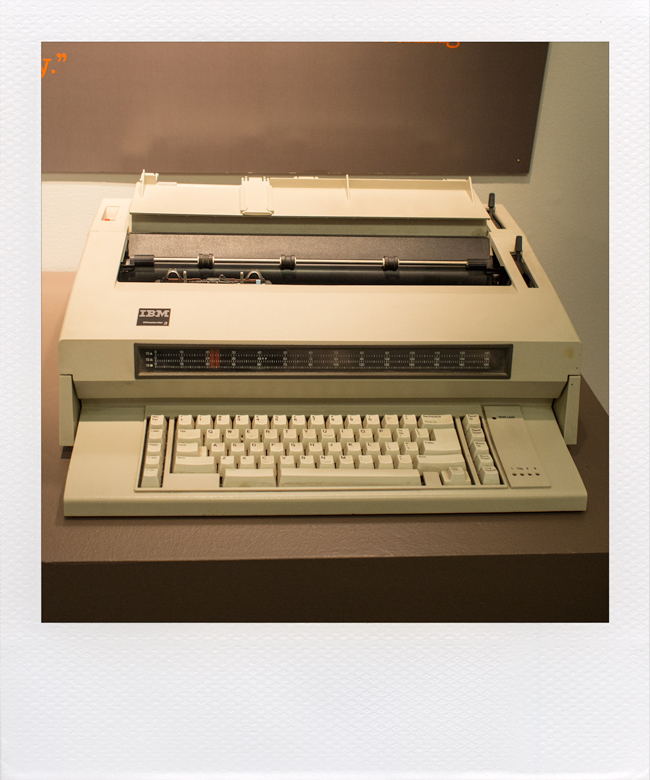

Sometimes the typewriters themselves harbor surprises. Soboroff tells of buying bestselling author Harold Robbins’s IBM Wheelwriter 3 from the deceased writer’s wife. "She said when he was typing, she could talk to him and he wouldn’t listen, she could throw water on him and he wouldn’t flinch, he would assume the role of his character while he was typing -- that's how intense people were with these things. She had not typed on the typewriter since he died, because this was his shrine. So on the ribbon when I pulled it out, you can read what’s written on it. It was his last book.”

The sheer volume of work that many authors produced on single machines is staggering. Ernest Hemingway, who often typed standing up, used only a few typewriters throughout his entire career. Brilliant in its simplicity, the typewriter was itself an inspiration to many, an open portal through which to channel inspiration. It’s easy to imagine that over extended periods of intense concentration, the user and machine began to share certain qualities, much like an owner and pet starting to show a resemblance. Or maybe writers chose the typewriters they did because of a connection they felt at the outset, an intuitive nod to the grueling and rewarding partnership they were entering into. As Hemingway put it, “There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”