Features

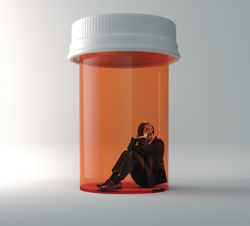

Lawyers who self-medicate to deal with stress sometimes steal from those they vowed to protect

Illustration by Justin Metz

But Corea's high-profile, extravagant lifestyle belied a serious problem that would eventually lead to an undoing covered in tedious detail by local media.

In 2013 he pleaded guilty to three counts of misapplication of fiduciary property and he's now serving a 25-year prison sentence in Texas.

How could a lawyer reach such professional heights, with all the trappings of success, only to crash and burn so spectacularly?

During a court appearance, Corea told the Dallas County Criminal District Court that he developed an addiction to Klonopin, a prescription drug that treats anxiety, and to other prescription medicine, including a seizure medication.

Corea's former attorney, John M. Helms Jr., adds more context, telling the ABA Journal that Corea wasn't making money the way he once was, and that he had marital problems. Helms says the personal and financial troubles led Corea to become someone entirely different from the person he envisioned himself to be when he graduated from the University of California's Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco some 20 years ago.

"He was taking medicine for [stress] and I think he started to become dependent on the medicine, so it became sort of a spiral," Helms says. "The stress got worse, the marital problems got worse, the practice got worse and the prescription meds use got worse."

Prosecutors alleged Corea took $3.8 million from 58 clients, who retained him for plaintiffs personal injury work. In addition to charges of misapplication of funds by a fiduciary, prosecutors charged Corea with theft, securing the execution of a document by deception and fraudulent use of identifying information.

If lawyers think that Corea's experience is particularly unique to him, Helms says they are mistaken. There are warning signs to watch for. Ask yourself: Do you feel like your professional life is out of control? Are you using alcohol and drugs to alleviate pressure, stress and sadness?

"I think it's important for law students and young lawyers to understand the kinds of personal situations and pressures that lawyers can face at different points in the practice," Helms says. "They also need to be told that the way to deal with it is not to try and work things out like a gambler would and think that they'll get the next jackpot and everything will be OK."

About 18 percent of attorneys in practice two to 20 years experience problem drinking, according to a 1990 study in the International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, compared with about 10 percent of the general population. Of those practicing 20 years or more, 25 percent were problem drinkers, the study states.

There's a widely held belief that lawyers struggle with substance abuse, depression and anxiety at a very high rate, says Patrick Krill, a former land-use lawyer in Los Angeles who directs the Legal Professionals Program at the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, the nonprofit alcohol and drug addiction treatment organization.

"But there is actually a paucity of current and reliable data on the behavioral health of attorneys," he adds. Krill's organization is working on a new study, with the American Bar Association's Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs, looking at substance abuse rates and patterns among lawyers, as well as mental health concerns. He expects the findings will be published this summer.

Counselors say that misappropriation of client funds usually occurs when money doesn't come in as a lawyer had expected, leading to stress in both personal and professional lives. Many self-medicate rather than getting help.

Illustration by Justin Metz

Shame is often a common trigger, says Krill, who is based in Center City, Minnesota. "It becomes a pattern of guilt, shame and self-medication," he adds. "That's especially likely when you have somebody who's involved with theft."

Lawyers who get caught often say that they intended to pay clients back. The attorneys who represent them say that's probably so, but many stumble as they get deeper in debt. The ABA's Standing Committee on Client Protection regularly surveys the administrators of lawyers' funds for client protection. Of the United States administrators who reported information, it was found that in 2013, a total of 936 lawyers were involved in claims approved.

If clients do get something back, it's often significantly less than what was stolen from them. Like many lawyers accused of stealing clients' money, Corea had no prior record of public discipline in the state where he practiced. So clients often have no reason to suspect anything until it's too late.

"He impressed me because he had a suite at the top of a building in downtown Dallas," says Glenda McCoy, who hired Corea to represent her in a wrongful death suit against Pfizer, the pharmaceutical company. The case settled for $225,000 in March 2012, but she never got the settlement money, reportedly because Corea kept it all for himself. Instead, she accepted a $40,000 award in 2014 from the Texas Compensation to Victims of Crime Fund, the State Bar of Texas' client security fund, which caps awards at that amount.

Clients may not notice when a lawyer is having a hard time, but other lawyers do. Yet they are often reluctant to say anything, because they don't have direct knowledge of behavior that violates professional conduct rules, says Terry L. Harrell, executive director of the Indiana Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program in Indianapolis.

"With personal problems, often you only see the tip of the iceberg and don't know exactly what the problem is or what is going on," says Harrell, who serves as chair of the ABA's Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs. Most programs offer referrals and peer assistance, she says, as well as consultation and sometimes facilitation for interventions.

People seeking help for addiction or mental health problems often fear that lawyer assistance programs will share information with attorney discipline agencies. What they don't realize is that many states extend attorney-client privilege to LAP staff and, Harrell explains, that LAP staff often have no duty to report misconduct to regulation agencies, including behavior that involves stealing client funds.

What are the signs that someone might be having problems?

"If someone is not functioning, that's all you need to know to go talk to them," Harrell says. It can be a very emotional conversation, which is why most avoid it.

"Could someone get angry and defensive? Absolutely," she says, mentioning ways to approach people. True concern is a good place to start. Maybe note that the person is missing more work, she says, or that you've noticed they don't laugh like they used to.

"You want to get them to start somewhere and at least talk to a family doctor."

If the person's response is that they're struggling but will be OK, Harrell adds, let them know you are available if needed.

"So if they do realize they're at a point where they need help, you are someone they can come to," she says. "You're not there to criticize or get them into any trouble; you just want to help. And admit that you don't understand everything that's going on."

She also advises having steps in place, should the person come to you for help. Calling your state's lawyer assistance program works well.

"A pretty large number of friends call and ask if the program is really confidential. As soon as I convince them 100 percent that I can't take anyone's law license, they put the person on the phone," Harrell says. "Then it quickly becomes a self-referral."

Lawyers in Bend, Oregon, may wish they'd taken the initiative to approach their state bar's attorney assistance program about Bryan W. Gruetter, who was accused of taking $1.1 million from clients.

According to a November 2013 U.S. district court filing, Gruetter diverted client retainers and settlement funds through wire transfers. He and others used the money to pay for personal and business expenses. His crimes took place between 2008 and 2012.

After Gruetter's arrest, other Bend lawyers told the State Bar of Oregon's Client Security Fund Committee that they often saw him at restaurant bars on weekdays around lunchtime playing video poker, says Steven R. Bennett, a Portland lawyer who chaired the committee.

Gruetter pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit wire fraud. He received a 63-month sentence with three years of supervised release. Bryan Lessley, a federal defender who represented Gruetter, did not respond to interview requests.

The Oregon State Bar assumed control of Gruetter's firm in 2012 after 19 people complained. Gruetter, who resigned from the state bar, didn't have a record of public discipline before 2012, so clients had no reason to think he would steal from them. Indeed, he was a former Oregon State Bar ethics committee chair.

Gruetter's petition to enter a guilty plea stated that he suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and bipolar 1 disorder, also known as manic depression. A prohibition on gambling is included in Gruetter's supervised release conditions.

"He was very good at hiding things. He'd be gone for weeks at a time and would tell people that he was sick or someone died," says Tim Williams, a Bend personal injury lawyer. "Clients would ask him for a meeting, and he'd cancel at the last minute."

Williams mentions a client who left him for Gruetter. She had called Williams, who was in a deposition and couldn't call her back immediately. She was anxious about her case, Williams says, and later that day she fired him and hired Gruetter.

Gruetter acknowledged that Williams' firm had done substantial work on the case and agreed to pay him a $50,000 referral fee. Williams eventually got the money, after various excuses from Gruetter.

The woman received her portion of the settlement, too, but she later found out that Gruetter didn't pay her medical providers. They sued her, and Gruetter defended the case for free, says Williams, a partner with Dwyer Williams Potter. She lost in arbitration, and Gruetter appealed. He did not respond to the motion for summary judgment that the providers' lawyers filed, and a default judgment was entered against the woman.

The medical providers started a collections process against the woman, and her wages were garnished, says Williams, who now represents several of Gruetter's former clients. He found out that Gruetter often told clients he was keeping all or part of their money to cover outstanding liens. He also told clients that if they waited long enough, the lien holders would abandon their claims and the client would wind up with more money.

That never happened, Williams adds.

"The thing about personal injury work is that clients have to hold out hope that they will get something at the end of the day. They're always hoping to get more," Williams says. "I think that's the way he was so successful stealing—it was the promise of more."

The Oregon State Bar's Client Security Fund paid 43 of Gruetter's former clients a total of $938,704. Some of the claim amounts were in the six figures, but each award was capped at $50,000.

The claims exceeded the fund reserve balance in 2012, but were investigated and paid over a period of two years, says Bennett, a partner with Farleigh Wada Witt. The Client Security Fund assessment, which is paid by active members of the Oregon State Bar, was raised from $15 a year to $45 to build the reserve back up.

As of September 2014, 52 applications related to Corea were approved by the Texas bar's client security fund, says Claire Mock, public affairs counsel for the bar's office of the chief disciplinary counsel.

According to Helms, Corea didn't intend to steal money.

"I think he certainly mishandled trust accounts. But I don't think his intention was simply to take people's money and run away. I think he intended to pay them back at one point," Helms says. "The problem was that as his law practice experienced financial difficulties, his ability to keep the firm operating was much harder than he thought it would be, and he allowed client funds to be used for that purpose, hoping and believing that a big hit was just around the corner."

Corea—who started his practice in Arizona and later moved with his family to Texas, where he joined Dallas' Bickel & Brewer—at one point had a successful debt-collection practice representing creditors. Much of the work involved default judgments, and he opened his own Dallas firm in 2003.

A significant amount of the collection cases were in the Navajo Nation court, Helms says, until Corea was suspended by the Navajo Nation Bar Association in 2009 for routinely requesting hearings held by telephone. According to the suspension notice, Corea claimed to have approximately 600 cases, 200 of which were in the tribal courts.

In 2010 the State Bar of Arizona publicly censured Corea. According to the finding, a Navajo Nation judge determined that Corea repeatedly used a dismissed Texas case to make it look like he had a scheduling conflict so he could get telephone appearances, rather than travel to court locations in Arizona. He also violated a court order directing him to transfer his tribal court cases to another lawyer by a certain date.

Around the time of his suspension by the Navajo bar, Corea switched his practice to plaintiffs personal injury work. He tried to set up a high-volume, assembly line practice, much like he had done with the debt-collection cases.

Unlike debt collections, Helms says, Corea's personal injury work couldn't run like an assembly line.

"The cases were different from each other, and there were more expenses associated with them," Helms says.

It's unclear what sort of trial or court experience Corea had when he started his personal injury practice.

"I asked him that, but I didn't push it," says Helms. "I think that Tom had a very high level of confidence in his own abilities, since he'd had so much success earlier."

Soon after Corea's theft arrest, he filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy protection. Listed as unsecured creditors were CBS Outdoor, which sells advertising space, and Dallas-area affiliates of MundoFox, CBS, Fox and NBC. Together, the claims are worth more than $255,000.

"He kind of appeared out of nowhere in this heavy marketing campaign. I don't know anybody who has ever seen him in a courtroom," says Michael J. Hindman. A plaintiffs personal injury lawyer with Dallas' Rolle, Breeland, Ryan, Landau, Wingler & Hindman, he represents three clients against Corea. Two, a former client and a health care provider, are creditors.

As for the likelihood of more lawyers encountering problems like Corea's, Hindman responds: "I don't think anything happened to Tom Corea other than Tom Corea. If you're going to do plaintiff work, you need to understand going into it that it's a roller coaster," he adds. "If you decide to live your life like your best month is going to happen over and over again, you've got no chance."

The Arizona bar public censure for Corea is not listed in his Texas bar information. The Texas bar requires that members provide it information about out-of-state discipline, says Lowell Brown, the agency's communications division director, and it did not receive information about Corea's censure.

After Corea was evicted from his law office, the landlord discovered the name of a Navajo Nation judge scrawled on the walls. The vandalism also included the judge's phone number, disparaging comments about her and drawings of penises. This happened after Corea's theft arrest, while he was out on bail.

Dirty toilet paper was found on the floor, the light fixtures and bathroom sinks were missing, and the steel jamb of the structure's loading doors was pulled from the frame, according to the Dallas Observer. When prosecutors presented evidence of the damage, estimated to be $200,000, to State District Judge Mike Snipes, he raised Corea's bail to $2 million. Corea was taken into custody.

Shortly after that, Corea hired Helms, a Dallas sole practitioner who previously was a large-firm partner and an assistant U.S. attorney.

"I was very curious about how all this happened," says Helms, who agreed to defend the case for a reduced fee.

Creditors' lawyers say the case was less complicated. "From the records we obtained and the witnesses we interviewed, it became apparent that Corea was using client funds to support a lifestyle of the rich and famous, and he was a real jerk about it. Corea was a guy who became a real monster, and he was living well outside his means," says Amy Ganci, an Allen, Texas, lawyer. She represents American Asset Finance, one of Corea's creditors.

Her client provides litigation finance and funding to lawyers, and Corea sold the business his attorney fee interest on a case for $90,000. Later, he reportedly forged a document to make it appear he'd paid the money back, and sold the same attorney fee interest to another company.

The case settled, she adds, and Corea took all the money, including his client's portion.

According to the Chapter 7 filing, Corea was $7.1 million in debt, and his assets were estimated to be worth $1.6 million. A substantial amount of his assets was tied up in his six-bedroom house in Palmer, Texas, a 280-acre property where his wife, Jennifer, bred, trained and showed quarter horses. The couple named the property Whistlestop Ranch.

In 2010 Corea told GoHorseShow.com that he settled a class action pharmaceutical case for $30 million. And his law office was in the Renaissance Tower, one of downtown Dallas' most fancy high-rises.

The Moinian Group, which owns the Renaissance Tower, is listed as an unsecured creditor in Corea's bankruptcy filing, with a $300,000 claim.

It might seem unlikely that someone could settle a case for $30 million and file for Chapter 7 bankruptcy two years later.

"Anything's possible. He played a lot in the quarter horse world, which is very expensive, and he had a lot of toys that were expensive," Ganci says.

Whistlestop Ranch recently sold for $1.7 million. Jennifer Corea had a homestead interest in the property, Ganci says, and got approximately $400,000 from the sale, with the rest going to the bankruptcy court. Tom Corea filed for divorce in 2012, according to the Ellis County clerk's office, and it was finalized on Dec. 30, 2014.

Stories like Corea's are rare, says Kenneth L. Cunniff, a Chicago criminal defense attorney. He also thinks that some lawyers who steal clients' money never get caught.

Cunniff currently represents Curt Rehberg, a suburban Chicago real estate lawyer who last year pleaded guilty to taking more than $1.2 million from clients. The Illinois Attorney Registration & Disciplinary Commission placed an interim suspension on Rehberg, and in October Rehberg filed a motion to disbar himself.

McHenry County prosecutors alleged that Rehberg, an attorney based in Cary, Illinois, was involved with several trust accounts, and he never distributed the cash to beneficiaries. One of the charges dealt with a donation of more than $500,000 intended for St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.

Rehberg's problems started around 2003, when the Illinois ARDC gave him a public censure for neglecting a client's zoning matter and falsely representing the matter's status to the client.

He paid the client $106,000, which was difficult, says criminal defense lawyer Henry H. Sugden III of Crystal Lake. Another client was unhappy with a result Rehberg obtained for her, Sugden adds, and Rehberg paid her $12,000.

Four people worked for Rehberg, according to Sugden. Rehberg paid them all benefits, including 401(k)s, and gave them raises—even after the real estate market crashed.

"He was a good lawyer," Sugden says, "but a bad businessman."

According to McHenry County Court records, Rehberg filed for divorce in 2006, and in 2007 a mortgage foreclosure case was brought against him. He didn't have a drinking problem, according to Sugden, until the financial problems started.

"After the shit hit the fan, he'd go home thinking, 'How will I keep the doors open?' Then he'd start drinking," says Sugden, adding that Rehberg did go to the Illinois Lawyers' Assistance Program, and he's also completed a treatment program.

"I think Curt feels better already," Sugden says of his client, who was sentenced to serve nine years in prison.

Cunniff, who would not comment on Rehberg's case specifically, says that when lawyers come to him for criminal or attorney misconduct defense work, he asks about their background and often advises that they contact a lawyer assistance program.

"Because they think what's perfectly normal isn't," says Cunniff, who is of counsel with SmithAmundsen, "they come away from LAP dramatically improved in their lives. Even if they end up losing their license or going to jail, they are eternally grateful."

If you want to cut back or stop using a substance, but haven't been able to do so, you might have an addiction issue, according to Krill. He also mentions cravings, repeatedly using a substance—even if it puts you in danger—giving up important activities because of substance use, and continuing to use, even when it causes relationship problems.

Admitting that they need help, Krill adds, is hard for many lawyers, and overall the profession does not offer much help.

"The professional climate within the legal profession tends to be emotionally isolating, rigorously demanding, anxiety-provoking and devoid of adequate consideration for any type of balance or personal wellness.

"Most attorneys wear their hard-earned ability to swim in such rough professional waters as a badge of honor. They aren't inclined to let others know they suddenly 'can't cut it,' " he says. "And it's that fear—that others will find out they're weak, vulnerable or troubled—that attorneys commonly tell me stands between them and getting the help they think they might need."

Related ABA Journal podcast:

Asked and Answered: "How can attorneys get help without harming their careers?"

This article originally appeared in the March 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Before the Fall: Lawyers who self-medicate to alleviate the stresses of the profession sometimes steal from those they've vowed to protect.”

Sidebar

Finding Support

When lawyers need addiction-related services, there are many organizations they—or someone who cares about them—can go to for help.

National Organizations

Alcoholics Anonymous

212-870-3400

http://www.aa.org/

Cocaine Anonymous

310-559-5833

http://www.ca.org/

Crystal Meth Anonymous

855-638-4373

http://www.crystalmeth.org

Gamblers Anonymous

626-960-3500

http://www.gamblersanonymous.org/ga/

Marijuana Anonymous

800-766 6779

https://www.marijuana-anonymous.org/

Narcotics Anonymous

818-773-9999

http://www.na.org

National Association of Anorexia Nervosa & Associated Disorders

630-577-1330

http://www.anad.org/

National Helpline for Judges Helping Judges

800-219-6474

http://www.texasbar.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Judges1&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=15127

Nicotine Anonymous

877-TRY-NICA

https://nicotine-anonymous.org/

Overeaters Anonymous

505-891-2664

http://www.oa.org/

Sex Addicts Anonymous

800-477-8191

https://saa-recovery.org

Sexaholics Anonymous

866-424-8777

http://www.sa.org/

State Organizations

Alabama

Alabama Lawyer Assistance Program

334-224-6920

https://www.alabar.org/programs-departments/alabama-lawyer-assistance-program/alap-foundation/

Alaska

Alaska Lawyers’ Assistance Committee

907-264-0401

https://www.alaskabar.org/servlet/content/lawyers__assistance_committee.html

Arizona

Member Assistance Committee

800-681-3057

http://www.azbar.org/sectionsandcommittees/committees/memberassistance

Arkansas

Arkansas Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program

501-907-2529

http://www.arjlap.org/

California

Lawyer Assistance Program

877-527-4435

http://www.calbar.ca.gov/Attorneys/MemberServices/LawyerAssistanceProgram.aspx

The Other Bar

800-222-0767

http://www.otherbar.org

Colorado

Colorado Lawyer Assistance Program

855-208-1168

http://www.coloradolap.org/

Connecticut

Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers

800-497-1422

http://www.lclct.org/

Delaware

Delaware Lawyers Assistance Program

877-652-2267

http://www.de-lap.org/

District of Columbia

D.C. Bar Lawyer Assistance Program

202-347-3131

http://www.dcbar.org/bar-resources/lawyer-assistance-program/

Florida

Florida Lawyers Assistance

800-282-8981

http://fla-lap.org/

Georgia

Lawyer Assistance Program

800-327-9631

http://www.gabar.org/committeesprogramssections/programs/lap/index.cfm

Hawaii

Attorneys and Judges Assistance Program

800-273-8775

http://hawaiiaap.net/

Idaho

Idaho Lawyers Assistance Program

208-323-9555

http://isb.idaho.gov/member_services/lap.html

Illinois

Lawyers’ Assistance Program

800-LAP-1233

http://illinoislap.org/

Indiana

Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program

866-428-JLAP

http://www.in.gov/judiciary/ijlap

Iowa

Iowa Lawyers Assistance Program

800-243-1533

http://www.iowalap.org/index.html

Kansas

Kansas Lawyers Assistance Program

888-342-9080

http://www.kalap.com/

Kentucky

Kentucky Lawyer Assistance Program

502-564-3795

http://www.kylap.org/

Louisiana

Lawyers’ Assistance Program

866-354-9334

http://www.lsba.org/lap/

Maine

Maine Assistance Program for Lawyers and Judges

800-530-4627

http://www.me-lap.org/

Maryland

Lawyer Assistance Program

800-492-1964

http://author.msba.org/publications/barbulletin/2013/may/lawyerassistance.aspx

Massachusetts

Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers

1-800-525-0210

http://www.lclma.org/

Michigan

Lawyers and Judges Assistance Program

800-996-5522

http://www.michbar.org/generalinfo/ljap/

Minnesota

Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers

866-525-6466

http://www.mnlcl.org/

Mississippi

Lawyers and Judges Assistance Program

601-948-4475

http://www.msbar.org/programs-affiliates/lawyers-judges-assistance-program.aspx

Missouri

Missouri Lawyers’ Assistance Program

800-688-7859

http://www.mobar.org/molap/

Montana

Montana Lawyer Assistance Program

888-385-9119

http://www.montanabar.org/?page=LAP

Nebraska

Nebraska Lawyers Assistance Program

888-584-6527

http://www.nebar.com/?page=NLAP

Nevada

Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers

866-828-0022

http://www.nvbar.org/lcl

New Hampshire

New Hampshire Lawyers Assistance Program

877-224-6060

http://www.lapnh.org/

New Jersey

New Jersey Lawyers Assistance Program

800-24-NJLAP

http://www.njlap.org/

New Mexico

New Mexico Lawyers and Judges Assistance Program

Judges: 888-502-1289

Lawyers and Law Students: 800-860-4914

http://www.nmbar.org/nmstatebar/Membership/Lawyers_Judges_Assistance/Nmstatebar/For_Members/Lawyers_Judges_Assistance/Lawyers_Judges_Assistance.aspx

New York

New York State Bar Association Lawyer Assistance Program

800-255-0569

https://www.nysba.org/LAP/

Nassau County Bar Association Lawyer Assistance Program

888-408-6222

http://www.nassaubar.org/For%20Our%20Members/Lawyers%20Assistance%20Program.aspx

New York City Bar Lawyer Assistance Program

212-302-5787

http://www.nycbar.org/lawyer-assistance-program/overview

North Carolina

North Carolina Lawyer Assistance Program

704-892-5699

http://www.nclap.org/

BarCares

800-640-0735

http://www.ncbar.org/members/barcares/

North Dakota

North Dakota Lawyer Assistance Program

800-472-2685

https://www.sband.org/Resources%20for%20Lawyers/Lawyer%20Assistance%20Program/about.aspx

Ohio

Ohio Lawyers Assistance Program

800-348-4343

http://www.ohiolap.org/Index.htm

Oklahoma

Lawyers Helping Lawyers

800-364-7886

http://www.okbar.org/members/LawyersHelpingLawyers.aspx

Oregon

Oregon Attorney Assistance Program

800-321-OAAP

http://www.oaap.org/2011/

Pennsylvania

Lawyers Concerned for Lawyers

888-999-1941

http://www.lclpa.org/

Rhode Island

Lawyers Helping Lawyers

800-833-0453

https://www.ribar.com/For%20Attorneys/LawyersHelpingLawyers.aspx

South Carolina

Lawyers Helping Lawyers

866-545-9590

http://www.scbar.org/MemberResources/LawyersHelpingLawyers.aspx

South Dakota

State Bar of South Dakota Stress and Depression Resources

605-224-7554

http://sdbar.net/

Tennessee

Tennessee Lawyers Assistance Program

877-424-8527

http://www.tlap.org/

Texas

Texas Lawyers’ Assistance Program

800-343-8527

http://www.texasbar.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Texas_Lawyers_Assistance_Program

Utah

Utah Lawyers Helping Lawyers

800-530 -3743

http://www.utahbar.org/members/lhl-blomquist-hale/

Vermont

Vermont Lawyers Assistance Program

800-525-0210

http://www.lapvt.org/

Virginia

Lawyers Helping Lawyers

877-545-4682

http://dev.valhl.org/

Washington

Lawyers Assistance Program

855-857-9722

http://www.wsba.org/Resources-and-Services/Lawyers-Assistance-Program

Judges Assistance Program

206-727-8268

http://www.wsba.org/Resources-and-Services/Lawyers-Assistance-Program/Judges-Assistance-Program

West Virginia

Lawyer Assistance Program

304-553-7232

http://www.wvbar.org/lawyer-assistance-program/

Wisconsin

Wisconsin Lawyers Assistance Program

800-543-2625

http://www.wisbar.org/forPublic/HelpforLegalProfessionals/Pages/help-for-legal-professionals.aspx

Wyoming

Wyoming Lawyer Assistance Program

307-472-1222

https://www.wyomingbar.org/for-lawyers/lawyer-assistance-program/