When British wildlife photographer David J. Slater embarked on a mission to save an endangered and uncannily human-like primate species in Indonesia by raising awareness via photography and money through photo sales, he had no idea he'd end up making headlines...and no profit. He is now receiving legal counsel regarding a potential lawsuit against the Wikimedia Foundation, as their three-year battle over the now famous "monkey selfie" has implications for copyright law and photographers worldwide.

The story begins in the summer of 2011, when Slater traveled to a volcanic tropical forest north of Sulawesi, Indonesia, to take photos that would bring the personality and plight of the Celebes crested macaque to public attention. He spent three days "slashing through tangled and very humid jungle…with a 20-kilogram backpack on full of expensive camera gear" and was rewarded with one truly remarkable experience, which he describes on his website. It occurred when the group of 25 or so monkeys he had been following that morning halted for a rest and grooming break. Slater sat nearby and snapped a few photos, remaining mindful of the "monkey etiquette" that he had learned "from many previous encounters around the world."

"After some time," he writes in the 2011 post, "a few brave monkeys began to come closer, and slowly but surely began paying me more attention." He let them groom him for a while, increasing their comfort in his presence, and then set the self-timer on his camera and positioned it on a beanbag on a log. When he reached out his hand, one monkey grabbed his finger—a moment that the auto-timer captured just before another monkey grabbed his camera. A few frames of green-and-brown forest blur later, the camera was back under Slater's control, but now he had a new idea: "I put my camera on a tripod with a very wide angle lens, settings configured...to give me a chance of a facial close up if they were to approach again."

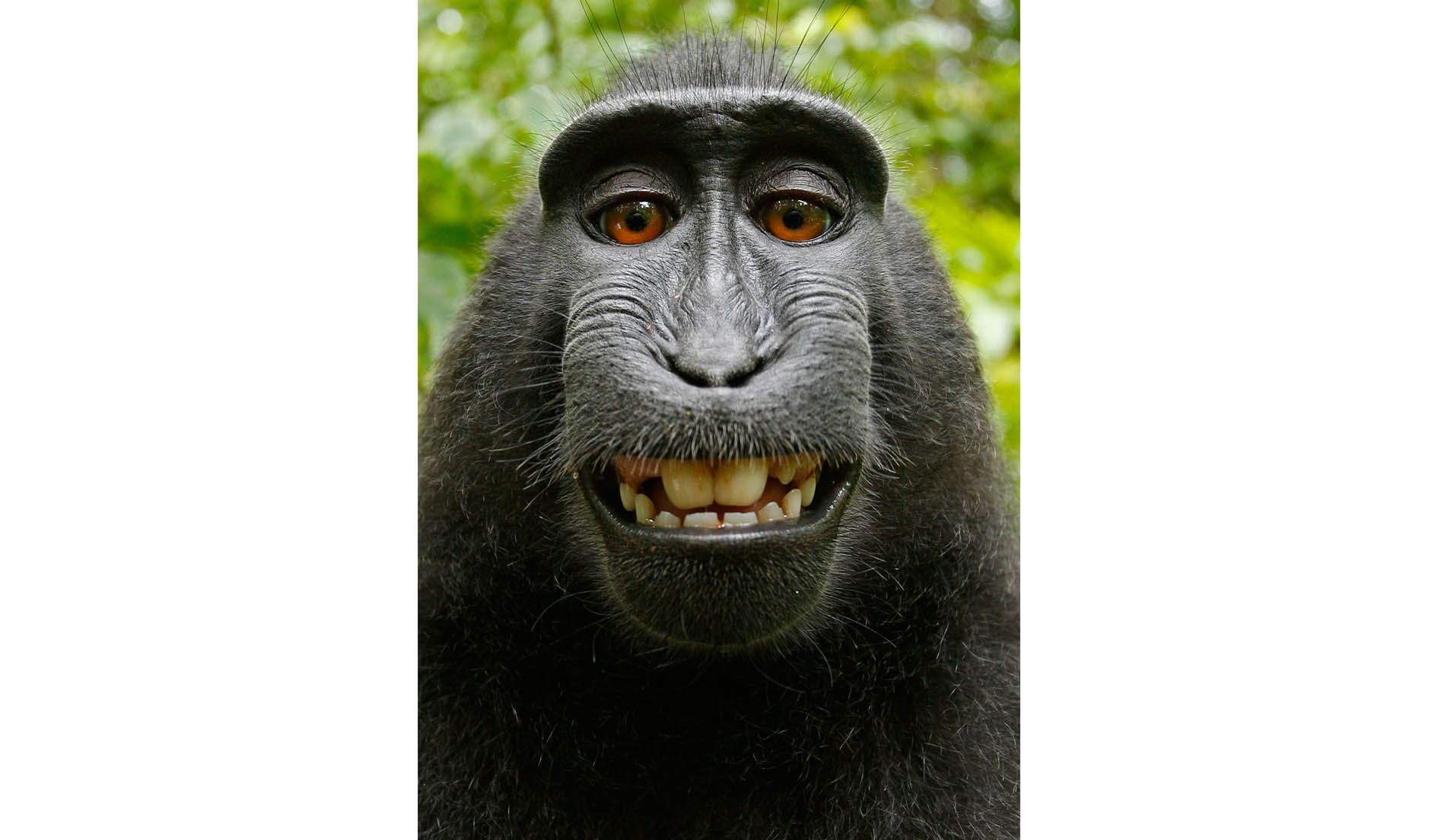

And just as Slater anticipated, that's exactly what they did. He describes watching the monkeys play with "the toy, pressing the buttons and fingering the lens," an event that filled him with "the joy of seeing your…baby learn about something new." Slater "had one hand on the tripod," while "they grinned, grimaced and bared teeth at themselves in the reflection of the large glassy lens," taking photos that soon went viral as the first-ever "monkey selfies."

As the word selfie did not enter mainstream use until 2012, self-portrait was the term used in the 2011 British tabloid article that launched the photos into fame. Slater says the Daily Mail used quotes and information from "a press release [his] agent sent out to promote a fun story." The reporter embellished the fun aspects of the story rather than accurately detailing the logistics of the photo shoot. The article's hook even included a false statement: "To capture the perfect wildlife image, you usually have to be in exactly the right place at precisely the right time. But in this instance, David Slater wasn't there at all and he still got a result." Once this tabloid article initiated the rumor that the famous photos were taken when "Mr. Slater left his camera unattended for a while," the photographer's blog and word were no longer the authoritative account of the situation.

The world took delight in Slater's "monkey selfies," but a Wikipedia volunteer editor took more than just that. In 2011, two of the images from the Daily Mail article were uploaded onto Wikipedia, meaning that they were also automatically added to Wikimedia Commons, which advertises itself as "a database of…freely usable media files." Instead of providing licensing information for the photos, the editor who uploaded them declared, "This file is in the public domain, because as the work of a non-human animal, it has no human author in whom copyright is vested."

When Slater discovered his photos on the Commons, he called Wikimedia and requested that the images be removed. A volunteer editor at the helpline removed the images, but they were restored by other editors following a user community discussion. Slater was not notified of the restoration. "I had to find out [for] myself," he says, "And since they've put it back up, they've absolutely refused my requests via editors of Wikipedia to take it down."

The Wikimedia Foundation's transparency report reads: "We received a takedown request from the photographer, claiming that he owned the copyright to the photographs. We didn't agree, so we denied the request." They do not agree, because "copyright cannot vest in non-human authors" and "when a work's copyright cannot vest in a human, it falls into the public domain." However, this position hinges on the foundation's independent assertion that, in the case of Slater's monkey photos, "no human agent made substantial creative contributions to the final image[s]." Slater asserts that he did make substantial creative contributions.

Many intellectual property lawyers side with Slater. "We here think that the image is not in the public domain," says Maurice Harmon of Harmon & Seidman LLC, a Colorado-based practice limited to copyright infringement. He was one of the four attorneys—each from a different firm that specializes in art law—who spoke to Newsweek on the topic. None of them found the Wikimedia Foundation's argument conclusive.

James Lorin Silverberg, the director of litigation and founder of the Intellectual Property Group, a boutique firm with offices in Manhattan and Washington, D.C., called Wikimedia's stance "a very shortsighted view to take." Though he acknowledged that "the copyright law doesn't pertain to authorship of monkeys," he said Wikimedia "may need to look quite a bit further for a legal solution, because Mr. Slater seems to be asserting authorship—not authorship of the work done by the monkey but authorship of the work done by him."

Silverberg spoke about copyrightable work that may have gone into the front and/or back end of production, comparing Slater's authorship over the composition of the scene to that of a photographer who envisions and stages a photo but has an assistant press the shutter release button. He also compared the editorial revisions and decisions Slater made while developing the image to the work that earns lithographic reproductions of paintings their own separate copyrights.

Furthermore, Silverberg says, "if you need to befriend the monkeys in order to get them to be present in front of the camera, you're working on trying to put together or gather together a composition." He says the author is not necessarily the person who pressed the button that took the picture but rather "the person who really made the creative contribution to the photograph"—the one "to whom the overall appeal of the work owes its origin."

The attorney adds, "Had Mr. Slater not done what he had done with the camera…the monkey would not have that picture."

Mickey H. Osterreicher, general counsel of the National Press Photographers Association, echoed Silverberg, saying, "These monkey selfies didn't just happen in a vacuum." As he sees it, Wikimedia is "taking someone's work without permission, or credit, or compensation," and its "whole argument is not only disingenuous but also self-serving."

After reading aloud directly from the Constitution's Copyright Clause, Osterreicher says, "The whole idea behind both U.K. and U.S. copyright law is to encourage people to create things. It's not to set up these self-serving questions."

The individual from Wikimedia U.K. who spoke to Newsweek acknowledged that "if the image was actually composed by and the settings set by the photographer, then that becomes a slightly different thing." To that he quickly added, "But of course then it's not necessarily a selfie." Though Wikimedia U.K. is separate and independent from the Wikimedia Foundation, he affirmed the foundation's repeatedly stated position, saying, "If it is genuinely a monkey selfie, then nobody can claim copyright on it, and it's available for anyone to use."

That Wikimedia encourages the use of media files from its Commons troubles Slater, who says, "People in China, Hong Kong, Bolivia, wherever can be putting [these photos] in some T-shirts or company brochures…I don't know whether this is going on." Had Wikimedia not placed the images in this "database of...freely usable media files," anyone who wanted to use them would have contacted Slater's representatives at Caters News Agency to negotiate a license fee, which would have compensated the photographer. Slater says, "Now other people make a living out of it, whereas my career, my income…has fallen to negligible, to say the least."

"Photography these days is just being devalued," laments Osterreicher, who sees Wikimedia's actions and assertions as not helping the situation. The attorney adds, "Far too many people believe that the public domain is a place and that place is the Internet." In his opinion, "this is a mob mentality of entitlement."

For Slater, "one good thing about this story" is that it may help educate the public about "what copyright means"—something that not even major corporations seem to understand.

Last year's big copyright infringement case resulted in a loss for the corporation and a victory for the photographer. Oddly enough, it was the infringing party that filed the lawsuit: Agence France-Presse (AFP), which took from Haitian photographer Daniel Morel's TwitPic account photos he posted immediately following the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti. AFP's U.S. partner, Getty Images, distributed Morel's images widely, collecting tens of thousands of dollars in revenue, as they appeared on CBS, ABC and CNN and in The Washington Post. AFP responded to Morel's lawyer's cease-and-desist letters by filing a defamation lawsuit—a move it probably came to regret after Morel countersued for copyright infringement and ended up winning $1.2 million.

The attorney who represented Morel in that case, Barbara Hoffman, says that "under both U.K. and U.S. law" David Slater "has a very good case." Slater says he is "getting advice on which jurisdiction…to take this under." Unlike AFP, the Wikimedia Foundation will not be the one to initiate legal action. "They have a grab-and-sue-me-if-you-don't-like-it attitude," says Slater.

Getting him to the stand, however, will be exorbitantly expensive, as copyright cases must go to federal court. Osterreicher says that it usually costs more to bring an infringement claim to court than a win would be worth, and that "the people that infringe know this."

Slater may be able to raise funds for a legal challenge with the help of others who feel strongly that copyright law needs to be clarified and/or strengthened. "Photographers are outraged," he says, citing concerns about Wikimedia's argument making it "appear that any image now taken by a nonhuman—triggered by an animal, say, through a trip wire…or a robot" cannot be copyrighted.

Photography triggered by animals is more common than one would think, and it has had a history of being copyrighted. In fact, when National Geographic photographer Steve Winter won the title of 2008 Wildlife Photographer of the Year for his famous nighttime photo of a snow leopard in the Himalayas, he used motion-sensor-triggered cameras that automatically release the shutter when someone/something enters the frame. Sounding exasperated, Slater asks, "Are Wikipedia now going to steal that image off National Geographic or Steve Winter, put it on public domain?"

Despite popular belief, Wikimedia is not claiming that the monkey owns these photos. The foundation is, however, denying Slater's claims of ownership. It sees its actions as in line with its mission, which is to serve the world by collecting "content under a free license or in the public domain…to disseminate it effectively and globally." It speaks of empowering and engaging people by making information free and accessible, but Slater says that if such an ideology extends to art, "creativity will be stifled. It's going to have the opposite effect."

What kind of effect this case—should it come to fruition—may have on copyright law remains to be seen.

In the meantime, the wildlife photographer is turning his attention back to his original purpose: saving those monkeys. Facilitating this effort is the German company Picanova, a canvas printing service that shares the photographer's concerns about both copyright law and the macaques. With the help of Picanova, Slater is giving away (all you pay is shipping) 12-by-8-inch canvas prints of his most famous photo, and the sponsor promises that for each order placed, $1 ( £1 in the U.K.) will be donated to the Sulawesi Crested Black Macaques Conservation Project. Details can be found on either Picanova or David Slater's website. The campaign ends November 30, and the voucher code is #MONKEYSELFIE.

* * * * * *

This article has been updated to clarify that the Wikimedia Foundation did not upload the photos to the Commons; they were added by volunteer editors of Wikipedia. Also, Wikimedia says that it never received a DMCA takedown request from David Slater or Caters News Agency; Slater disputes this and says that he has proof that he has shared with lawyers. In a previous version of this article, a Wikimedia quote was erroneously attributed to a statement; it was actually from Wikimedia's transparency report. We have also removed several statements given by Wikimedia U.K., because the Wikimedia Foundation says that Wikimedia U.K. is not qualified to address the issue.

Finally, on the day this article was published, the U.S. Copyright Office released an updated draft of their compendium on copyrightable authorship, and it included "a photograph taken by a monkey" as an example of work that would not be registered. Slater says, "I don't think it makes any difference to my case." Some American attorneys do not think it does, either. Maurice Harmon, a copyright infringement lawyer previously quoted in this article, recognizes authorship in "the photographer who chooses a lens, camera position, sets it up on a tripod…and causes the photograph to be made in a place and in a manner of his creation."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Louise Stewart is an undergraduate at Stanford University, majoring in English with a creative writing emphasis and joining Newsweek for ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.