The darkness made it difficult to photograph the blood-splattered pavement.

Since crime scene investigators had not yet arrived, the dozen or so photojournalists were able to shoot close-ups of the body that laid face down, curled up in the fetal position. As the herd of photographers inched forward, repositioning themselves to find more light, Brother Jun Santiago retreated. He wanted to capture the scene from a distance.

“I’m trying to get out of the brutality,” he said. “I want to capture the stench, the smell of the crime scene. The night is so powerful. The darkness is so powerful. Right now people are sleeping and they don’t know what’s happening.”

An unconventional resistance

Brother Jun is talking about the war on drugs in the Philippines, where more than 7,500 alleged drug addicts and pushers have been killed since president Rodrigo Duterte took office eight months ago.

Since December, Santiago has been documenting the nightly killings with local and foreign journalists on the graveyard shift in Manila to bring attention to the victims, mostly low-level drug offenders from urban poor communities. At night, he’s a photographer. During the day, he attends mass and fulfills his religious duties at the National Shrine of Our Mother of Perpetual Help in Manila, also known as the Baclaran Church.

With little else but a camera, Santiago has quietly led an unconventional resistance movement within the Catholic Church against the government’s war on drugs, although he would say he’s just a man of faith taking photos to help his community. While the hierarchy of the Church hesitated to speak out against the killings for seven months as thousands were killed, Santiago helped fill the void with his images.

Just before Christmas, his photos were blown up and displayed outside Baclaran Church along with the work of other photojournalists. The exhibit made national headlines, sparking intrigue and outrage. For many churchgoers, it was an introduction to the cruel truth of a brutal and lawless war.

“It was a unique way of exposing reality,” said Father Carlos Ronquillo, the rector of the Baclaran. “The power of images is something that I think can be harnessed if we as a church want to engage people to think deeply about what’s happening. Not only through words. Not only through preaching.”

Santiago’s position in the church allows him to be more involved in the community. Priests are generally too tied down with official duties to be as active in the daily lives of their parishioners. As a result, the flexibility has given Santiago room to establish a more comprehensive outreach program for victims and their families.

Concrete actions

In January, Santiago hired Dennis Febre, a human rights activist, to oversee the administrative side of the Baclaran’s extra-judicial killing (EJK) response program. The initiative provides a range of services for those affected by the drug war, including financial support for families, legal assistance, livelihood and employment programs, rehabilitation resources, and protection for those under threat. Febre is responsible for following up with the families of the victims Santiago documents at night. He also verifies cases of those who come to the church on their own for support.

“The concrete actions we are doing are really non-political,” said Febre. “We respect [Duterte] as the president of the country, but at the same time the government needs to respect human rights.”

Before the drug war, the Baclaran provided burial assistance of up to 5,000 pesos ($100) for families in need, but that hardly covers the full cost, which typically runs anywhere from 30,000 to 55,000 pesos.

“The families have no time to grieve. They’re always thinking of how to bury because the cost of the funeral services is too hard on them,” said Santiago.

The church realized it needed to do more. By mid-February, the Baclaran had paid all the expenses for 56 families to bury their dead. Dozens more are on a waiting list. Costs are funded by donations from hundreds of thousands of devotees who flock to the church every week. The Baclaran is one of the most attended churches in the country.

“Reign of terror”

This month, resistance within the Catholic Church has grown stronger. The Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines released a blistering statement on Feb. 5 condemning the president’s “reign of terror.” Two weeks later, thousands of Catholics marched in Manila against the “spreading culture of violence.” Condemnations of the drug war have become commonplace during mass in many parishes on Sundays, empowering more Catholics to speak out.

Still, Ronquillo, the superior at Baclaran, questions whether these developments are enough.

“The main question is what is the impact? We’re in a changed time. There’s been a certain alienation that has altered people’s receptivity to what the church is saying. We are in our convents, our churches and our schools, but we are not among the people generally,” Ronquillo said.

Santiago’s documentation and the Baclaran’s EJK program strike at the heart of that disconnect. While some Church leaders continue to remain quiet or offer ineffectual criticism through words at the pulpit, Santiago’s approach has paved the way for a new church order that prioritizes actions over words.

Duterte’s rhetoric sometimes makes that type of advocacy difficult to carry out. He has repeatedly lambasted the Church as “the most hypocritical institution,” even calling it “full of shit” as officials ramped up attacks against his anti-drugs campaign in January. When priests and bishops speak out against the crackdown, Duterte often accuses them of womanizing or being corrupt.

“He hits below the belt,” said Father Amado Picardal, who has criticized Duterte for decades dating back to his time as mayor of Davao in the country’s south.

In the beginning, fear and intimidation helped stifle opposition, according to Father Atilano Fajardo, public affairs ministry director of the Archdiocese of Manila.

“Thou shall not kill”

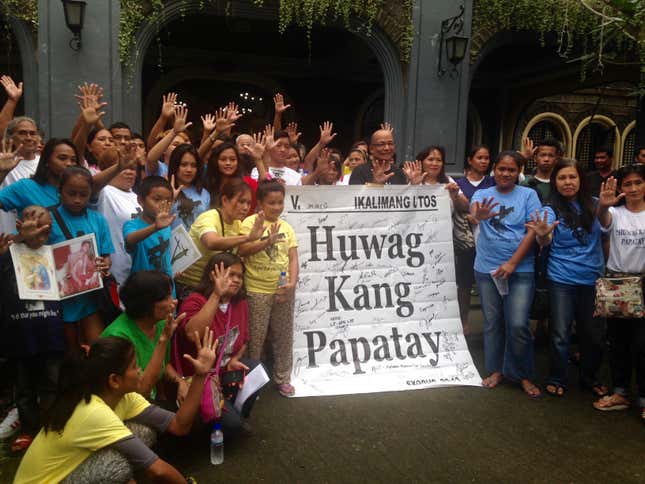

While many within the Church withheld criticism at the outset of the drug war to give Duterte more time to prove himself, Fajardo chose to mobilize. Less than a month into Duterte’s presidency, Fajardo launched a campaign against the drug war called Huwag Kang Papatay, which translates to “thou shalt not kill.” As one of the first priests to speak out, Fajardo disputes the idea that the Church hasn’t done enough.

“It’s not true,” said Fajardo, referring to criticisms that the Catholic Church didn’t do anything for months. “Go to the parishes. Get out of your subdivisions and see what the Church is doing.”

Beyond condemnations of the drug war during homilies, Fajardo points to the many parishes that are also offering rehab services, trauma counseling, and refuge for drug users and victims’ families.

He acknowledges, however, that these efforts “need to be accompanied by mass movements and actions.”

It is that belief that drives Fajardo to keep organizing and Santiago to continue covering the night shift. Without them, the dead remain nameless and the bodies become mere statistics.

“The people must say this is enough,” Santiago pleaded. “People must mobilize because the church cannot do it alone.”