“How long is the shelf life for your fruits since you guys don’t have electricity or somewhere permanent to keep them?”

John Mbindyo was buying groceries at his local store in Nairobi, when the 28-year-old IT graduate asked that question of his vendor. The store manager said, depending on the amount of stock, the goods last about two to three days. And then, he added: “I wish we had fridges to keep them cool.”

And so was born the idea for FreshBox, a solar-powered, walk-in cold room that provides retailers with storage facilities to preserve perishable products. Operating for five months, the project offers vendors and farmers refrigeration services for 70 Kenyan shillings ($0.68) a crate per day. “It hit me,” Mbindyo says. “There’s demand. This is possible. Why not try it out?”

Throughout the world, food waste and spoilage is a significant problem facing supply chains from farm to fork. The Rockefeller Foundation says one-third of all the food that is produced is never consumed—a staggering loss that would have fed the nearly 800 million people who are food insecure of undernourished worldwide.

The crisis is even more acute across Africa, a continent where the majority of people derive their livelihood from agriculture. Currently, more than 20 million people in northeast Nigeria, South Sudan, and Somalia are facing starvation. Yet, half of all the staple food in the continent is lost in the post-harvest stage or before they hit the market.

In Tanzania, for instance, nearly 40% of all grains are lost due to poor storage, costing the East Africa nation $332 million in revenues every year. In South Africa, despite increased production of food, 13 million people go to bed hungry partly because of inadequate storage facilities.

“Like manufacturing, agriculture needs to be supported by complete functioning systems from production to consumers,” says Calestous Juma, a Harvard professor and author of the book, The New Harvest, about agricultural innovation in Africa. “The solutions lie in building reliable energy, storage, processing, and transportation systems to support agriculture.”

But while there’s need to massively invest and improve the entire food system in Africa, there are small and large-scale technology projects hoping to stop the drain of food waste. The innovations around renewable or alternative energy are also paramount given that access and connection to electricity, especially in rural areas where food is produced, is still a luxury in many African countries.

Last year, the Rockefeller Foundation kick-started the YieldWise program, a seven-year multi-million dollar initiative to strengthen food systems. The foundation will work with governments and companies like Dangote Farms to provide metal silos and hermetically-sealed bags to smallholder farms. In Kenya, the project will promote solar drying and provide cold storage units to preserve crops.

The shift towards preservation is also taking place in rural and desert communities. Back in 2001, Nigerian Mohammed Bah Abba invented a pot-on-pot system that preserved produce for weeks instead of days. The two earthenware pots were fitted into each other, filled with wet sand, and the produce covered with a wet cloth. Bah Abba went on to sell as many as 12,000 pots.

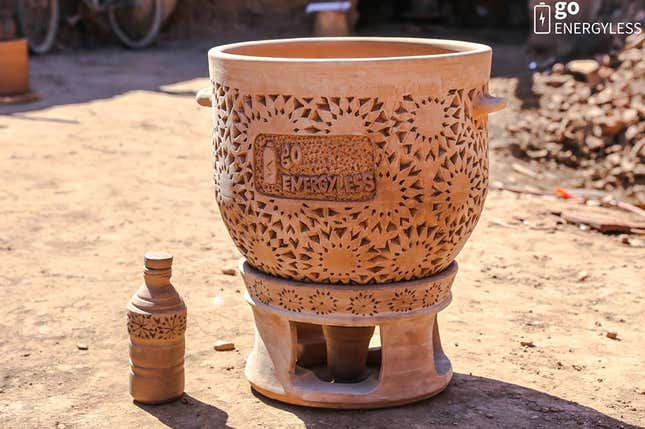

Go Energyless, a Morocco-based social enterprise also developed a natural low-cost cooler that can save food for over 13 days for people in remote areas. Its prototype is made with clay by local potters.

Evaptainers, a project that started in an MIT classroom, has also developed a mobile, electricity-free cooling unit that allows fruits, vegetables, and meat to be stored in one place.

Many of the innovative cooling units available, which could potentially save billions of dollars of food from waste, are also a reminder of the need to scale innovations with backing from investors in order to have a real impact on Africa’s agriculture ecosystem.

Since its establishment, FreshBox has engaged the services of 10 different vendors in Nairobi, and four different farmers in the neighboring Kiambu County. Mbindyo has also reached out to hundreds of farmers and retailers who say they are willing to purchase his services. “I am hoping to expand our capacity, and to have a number of units across Nairobi to attract more clients,” he said.

These kinds of tech investments, Juma says, is the best way to show communities that not all is lost on agriculture. “The work must start with securing the system in the first place,” he says. “One episode of rotting produce is enough to put off a community from increasing yields for a lifetime.”