'March 1917' follows Russia and the US in a year that shaped the future

Loading...

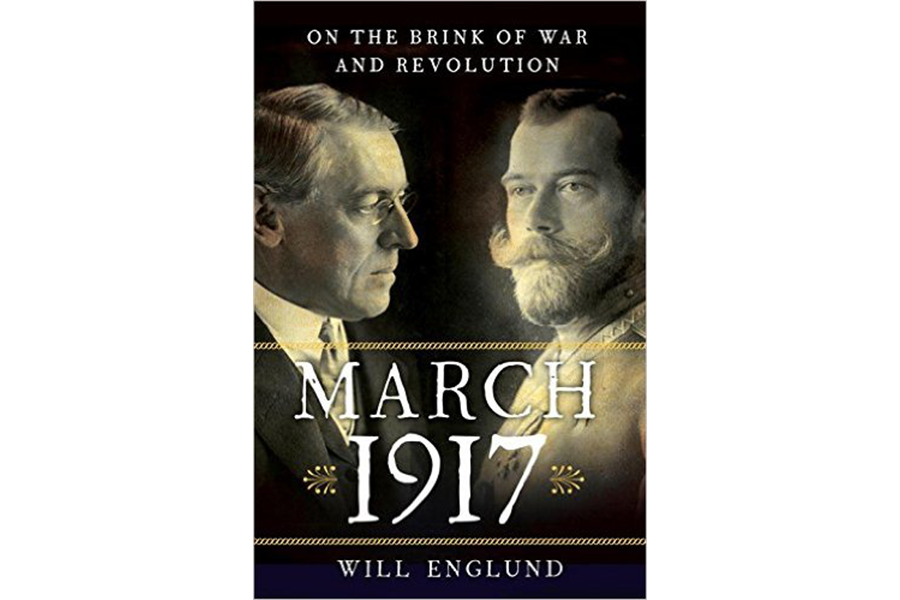

March 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the two events that form the support-columns for veteran news correspondent Will Englund's new book, March 1917: On the Brink of War and Revolution. First, Russian Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, ending centuries of Romanov rule. Second, the United States, led by President Woodrow Wilson, abandoned its official stance of neutrality toward the war grinding on in Europe and instead declared war on Germany. Englund's energetic, intensely readable book largely splits its narrative along the fault-lines of these two events; in deliberate and carefully-researched order, "March 1917" unfolds the events of not just the month but the whole year on which the future of half the world hinged.

Englund is hardly the first to characterize 1917 as a watershed year. The so-called February Revolution that rocked St. Petersburg in March of 1917 not only drove the Tsar from power but began the radical re-shaping of Russian rule that would then be galvanized by Lenin in the October Revolution, in which March's provisional government was scrapped in favor Bolshevism and the foundation-laying of what would become the USSR. In sure, economical strokes, Englund describes the hopeless gap that quickly widened between the country's new political realities and its well-intentioned but hapless former monarch; “From time to time someone would describe Nicholas, accurately enough, as a mild-mannered man, modest in his comportment, dedicated to his country,” he writes. “But that didn't make him a democrat.”

These revolutions were successful in large part due to the fact that the bloodletting of World War I had left the Tsar's main instrument of repression – the Russian army – in a state of more or less open mutiny, and this is one of the many ways the war, grimly but accurately summarized here as “millions of refugees, millions of wounded, millions of dead,” overshadows everything else in Englund's book. “The war,” he writes simply, “set both the United States and Russia on the paths they would follow for the next century.”

At every step of President Wilson's decision to respond to Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare – which treated all oceangoing vessels in the Atlantic, including US shipping, as fair targets – there were waves of fierce opposition throughout America. “Wilson saw himself as a righteous man,” Englund writes with a fair degree of diplomacy. “Though he could deliberate over a policy decision, once his mind was made up there was no changing it and no hope that he might compromise.” And his domestic foes were every bit as adamant; in that fateful March the Emergency Peace Federation, for instance, ran an ad in the New York Tribune: “Mothers. Daughters and Wives of Men – Have you no hearts? Have you no eyes? Have you no voice? We are being rushed to the brink of war – AND YOU DO NOT WANT WAR.”

Nor was the country ready; on the eve of war, the United States had scarcely a single trained division of soldiers at its disposal. And despite the vociferous war-mongering of former president Theodore Roosevelt, there was widespread national resistance to the idea of getting entangled in what most people saw as an entirely local European fight.

All such opposition was of course overcome, and two million American soldiers went off to fight, and as Englund points out, they came back to a substantially different country than the one they'd left, a looser, less formal country flush with wartime prosperity and a palpable sense of new standing in the world. “The American of the 1910s is a remote figure, living a different life from ours,” Englund writes. “The American of the 1920s is recognizably one of us.”

This tremendous surge of national pride happened despite the fact that, as our author points out, “Nearly all the arguments about the war turned out to be wrong”: it didn't make the world safe for democracy, as Wilson had naively hoped; it didn't break Germany's militaristic spirit; crucially, it didn't further the cause of the Russian Revolution abroad. An impartial observer in 1917 would almost certainly have predicted that the ultimate significance of the Russian Revolution would far overshadow the US's brief and hasty participation in a fight on the Continent.

In 2017 we know that such an impartial observer would have been quite wrong to think such a thing. The Russian Revolution gave birth to an implemented political ideology that hardly endured for a generation, whereas Englund is right to contend that World War I taught the United States the terrible appeal of interventionism: “The lesson of 1917 seemed to be that America had an obligation to set things right beyond its borders,” he writes, and this was only half of the change. The other half was the real birth of what President Eisenhower dubbed the military-industrial complex, which would go on for the next century to pursue war for profit motives rather than Wilsonian idealism. In this sense the careful history in "March 1917" also doubles as a warning.