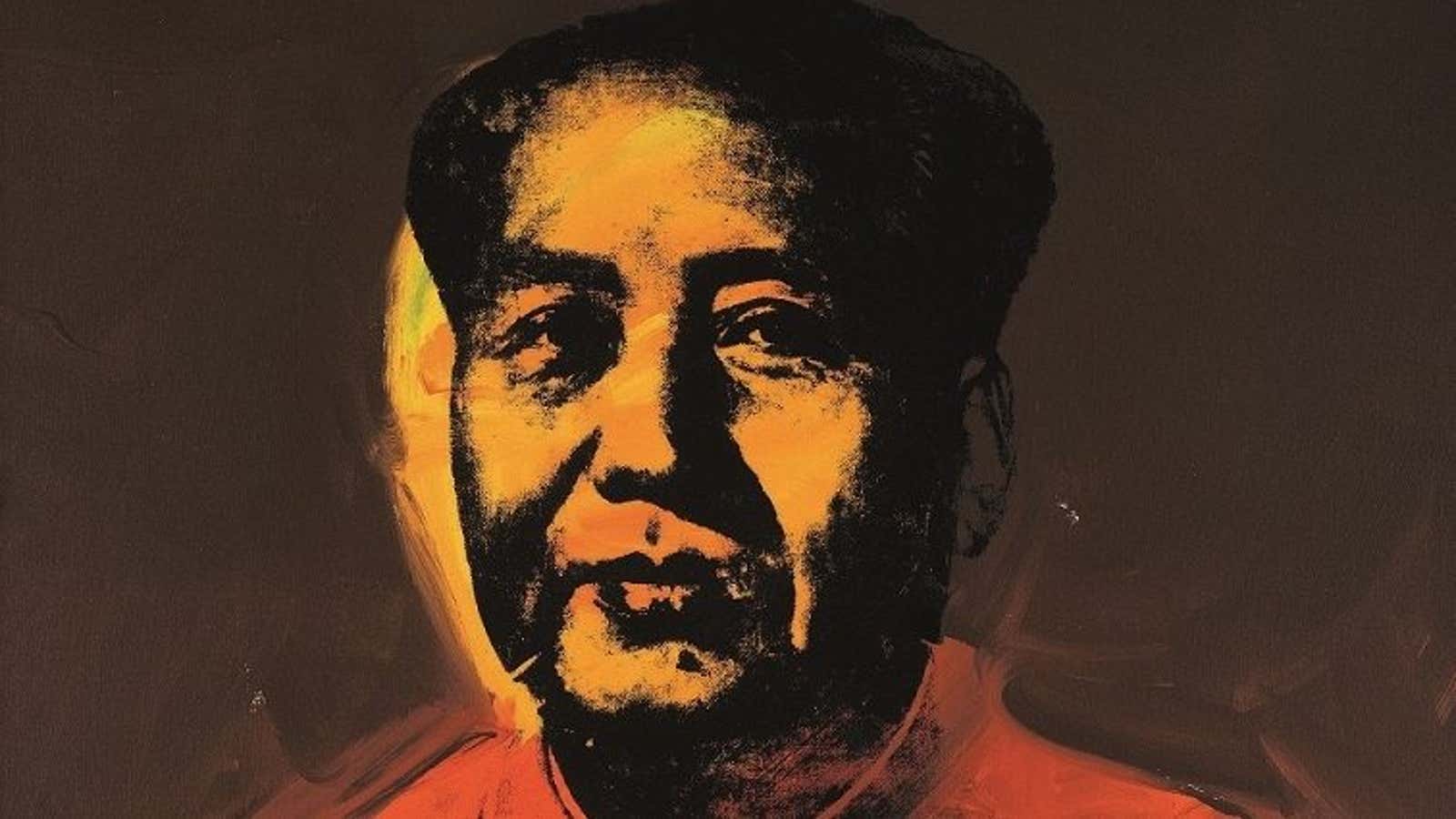

- When Richard Nixon visited China in 1972 it wasn’t just a seminal point for US-China diplomatic relations, it was also a turning point for pop art’s most important artist. A year after Nixon’s visit, Andy Warhol, who had stopped painting for eight years, began to work on what would become a series of portraits of Mao. One of these, estimated to be worth between $11.6 million and $15.5 million dollars, is set to be auctioned by Sotheby’s in Hong Kong on Sunday (April 2).

China’s communist leader might have seemed an odd choice for an artist known for his focus on the objects of everyday American life like Campbell’s soup cans and Coca-Cola bottles, but painting Mao encapsulated everything that made Warhol tick: fame, an image inherently pop due to its incessant mass reproduction by the Communist Party, and the possibility of subverting a communist icon into a commercial, consumeristic one.

In his memoir Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up, writer Bob Colacello remembers that Warhol’s Swiss dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, was trying to spur the artist to return to painting–a medium he had abandoned for eight years. Bischofberger suggested he do a portrait of “someone famous,” and thought of Albert Einstein, but, Colacello writes, Warhol replied he’d do Mao Zedong, since he was “the most famous person on earth.” (Warhol did also do a portrait of Einstein.)

The work to be auctioned Sunday is simply titled “Mao,” and is one of 28 oil-and-silkscreen inks on canvas painted in 1973. Fairly large at 50 by 42 inches, the picture is based on the most reproduced Mao Zedong portrait of all: the official photograph of the former Chinese leader’s head and bust with the iconic buttoned-up jacket, that at the time was to be found inside the “Little Red Book” of Mao’s quotes. The portrait that hangs from the gate to the Forbidden City at Tiananmen square in Beijing–and which is regularly changed for a fresh one, as China’s heavy pollution quickly makes its pastel colors grayer than intended–is also based on the same photograph.

The portrait to be auctioned in Hong Kong will be the first of Warhol’s Maos to be put on sale on Chinese soil, and leads a major sale of modern and contemporary art in the city. The work was last sold in 2014 in London to its present, unnamed owner, for US$12.2 million–Warhol’s paintings are among the most heavily traded art pieces–and the expectation is that it will fetch even more this time around. The most expensive Warhol in the Mao series is a $17.4 million large-scale portrait of the Chinese leader that was bought in New York by Hong Kong tycoon Joseph Lau in 2006.

It’s not clear that a Chinese collector will feel bold enough to snap up this impressive work. “Art that includes the likeness of Mao Zedong has become one of the few hard-and-fast taboos for the Chinese cultural authorities in recent years,” says Philip Tinari, director of the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing. That prickliness has returned in spite of the fact that many Chinese pop artists, undoubtedly inspired by Andy Warhol himself, have also been playing with Mao’s image, even though their works can rarely be seen in China.

The reduced tolerance for these images on the mainland became evident in 2012, when the traveling exhibition “Andy Warhol: 15 Minutes Eternal,” organized by the Andy Warhol Foundation, had to be stripped of its 10 Mao silkscreen portraits when it stopped in Shanghai and Beijing. Chinese artists and art lovers had surely seen reproductions of those works, but the authorities felt it wasn’t right to exhibit them in public. Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, China’s president and Communist Party secretary, the cult of Mao has gone through a noticeable revival. In January Deng Xiangchao, a professor of art at Shandong’s Jianzhu University was fired just for making remarks critical of Mao Zedong on social media–the latest in a long series of people to end up in trouble for daring to criticize the “Great Helmsman.”

Warhol in Post-Mao China

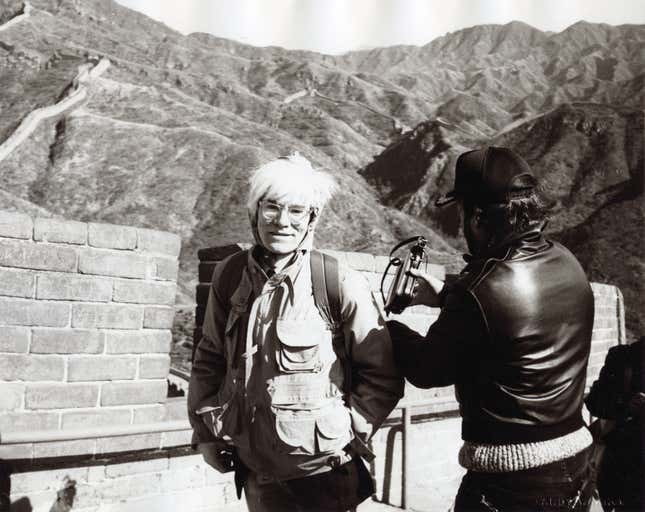

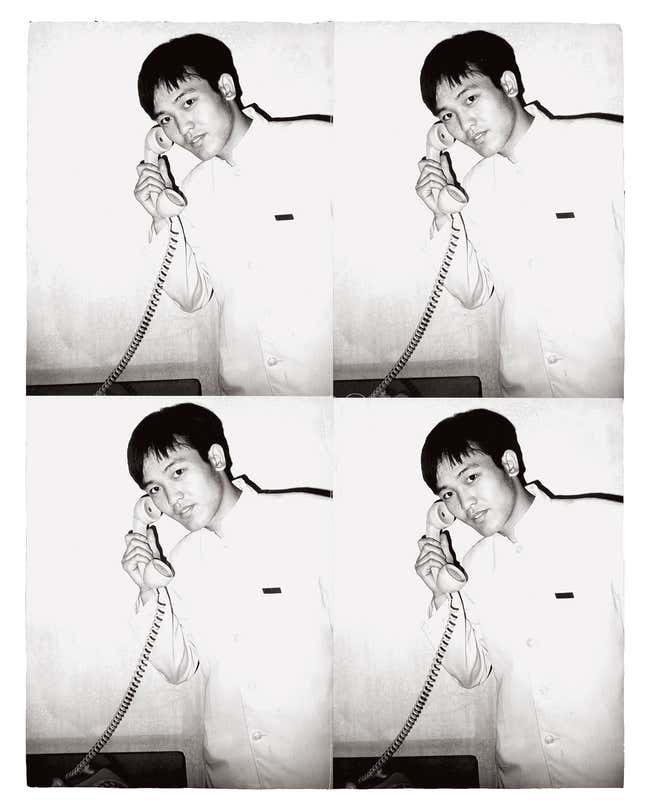

At the time he was painting his Mao series, Warhol had never been to China. It wasn’t until 1982 that, Warhol himself finally visited the country as it was just starting to open up. This month, the auction house Phillips has separately been hosting an exhibition in Hong Kong of the photographs that Warhol took during his trip–a series of black-and-white clichés that afford a glimpse of Warhol’s singular eye for the quirky detail in a setting vastly different from his New York hangouts.

Politically, it was still too early for an artist like him to be allowed to interact significantly with local artists, but his legacy is still felt today as one of the biggest influences on all art, in China as in the rest of the world. “Warhol will be relevant as long as we live in a media-saturated, commercially driven visual culture—that is to say, for the foreseeable future, particularly in China, where these trends continue to accelerate,” observes Tinari.

The Proliferation of Mao

At the same sale on Sunday, Sotheby’s will be auctioning two other Maos—both by Chinese artists. These include an oil by Wang Guangyi, “Mao Zedong OU,” a 1989 work estimated at under $200,000 that portrays the gray silhouette of the Chinese dictator on a red background as he raises his hand in salute, covered by a partial grid; and a work by Liu Wei executed between 1992-1999 called “Mao Generation.” Also an oil on canvas, it portrays two slightly stunned-looking children in the foreground, with a portrait of the Chinese leader made from the official Mao’s photo in the background. The work is set in a wooden frame embellished with numerous stylized carvings of the former leader.

It is hard to overstate the influence of Andy Warhol on modern Chinese artists. “He’s such a large figure in China,” says Alexandra Seno, Head of Development at Hong Kong’s Asia Art Archive, “also because Warhol’s idea that art is good business is so embraced by contemporary Chinese artists, it really resonates.”

Or perhaps what still resonates is what writer Bob Colacello saw in the portraits, according to the catalogue note: “They were all about power: the power of one man over the lives of one billion people.”