Predappio, Italy

The shops that line the main street of Predappio, a small town in Italy’s Sangiovese countryside, seem innocent enough—the biggest one is simply called “Predappio Souvenirs.” But it’s what’s inside that makes them remarkable: a vast collection of fascist memorabilia, including statuettes, towels, books, posters, and postcards covered in fascist symbols; and images and busts of fascism’s founder, former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. The window displays feature batons bearing Mussolini’s name or quotes, while pink and pale blue baby rompers are adorned with the dictator’s portrait and most famous slogans (“I don’t care!” and “We shall march forward!”), casually arranged as if they were any other kind of merchandise.

Predappio, population 6,400, is the birthplace of Mussolini, who was killed in 1945 by anti-fascist Partisan fighters as he fled to Germany in a Luftwaffe uniform. Under his rule, from 1922 to 1943, Italy’s democratic liberties were revoked, opponents were persecuted and executed, discriminatory racial laws were drafted, and the country was led into a disastrous role in World War II and two years of Nazi occupation. For most of his time in power, Mussolini enjoyed strong popular support among the majority of Italians.

It is hard to overstate the shock that these shops can cause visiting Italians to feel: the Scelba Law has made apologia del fascismo (“apology of fascism”) a crime in Italy since 1952, which means that the open display of fascist symbols and such public support for fascism itself are not a common sight. I decided to visit Predappio for the first time to learn about the Museum of Fascism that the town’s mayor, Giorgio Frassineti, of the left majority party Partito Democratico (Democratic Party) wants to build here, to counter the strain of nostalgia for fascism he feels has infested his town. Before setting off, I had been warned about the shops. I thought I was prepared. But I wasn’t. I never expected to see something so blatant, so aggressive, and so openly nostalgic for the fascist past. The very existence of these shocking shops represents, in a nutshell, all the ambiguity of Predappio, and of Italy’s relationship with its fascist past. It is hard to see how they could be considered legal, given the above mentioned Scelba law, and yet, law enforcers let them exist as if they were unable to see them, in spite of the outrage they have caused.

∞

A visit to Predappio can feel like an excursion into an alternative reality, one where fascism is displayed as a folkloric episode, and where revisionist history is displayed as fact. You wouldn’t find this type of scene anywhere else in Italy. Of course, fascist graffiti pops up from time to time in the country’s biggest cities; extreme right-wing soccer fans will raise their right arm straight in the air in the Roman salute while chanting their team’s name; and a neo-fascist group called Casa Pound (from the name of the British poet Ezra Pound, a fascist sympathizer) has attacked refugees, immigrants and left-wing opponents, while also developing an ideology that openly admires fascism. And yet, none of this compares to what a visitor sees in Predappio.

I arrived in this tiny town during an unseasonably warm February day. Had I come on July 29, Mussolini’s birthday, or April 28, the day of his death, or even worse, October 28, the anniversary of the March on Rome—the day Mussolini and his National Fascist Party took power—the experience would have been much more shocking. I would have encountered hundreds of black-shirted “nostalgici”—as the fringe groups who claim nostalgic fondness for the regime are often called—that come to Predappio to commemorate these events, and shout in front of the TV cameras that “he” was a much better politician than current ones.

For Frassineti, Predappio’s mayor, building the museum has become an urgent matter, as a number of pro-fascist parades and visitors have drawn increased attention to the town. “It is difficult for things to be any worse in Predappio than they are right now,” he says with barely suppressed impatience. “I’m hoping that a serious, sober, historically sound museum will get rid of the neo-fascists that come here, or at least contain them.”

While Mussolini was in power, Predappio became known as “the Duce’s Village,” and school children and groups of supporters were taken here on organized visits. Mussolini used architecture as one of his main propaganda tools, erecting monuments and apartment complexes at a pace never seen before in Italy. In the twenty years that he was in power, Predappio became Mussolini’s pet project, as he completely overhauled it to showcase some of his favorite styles, still clearly visible today. Its main road is flanked by palaces that show off the simple lines of the Italian Rationalist Movement (link in Italian), and the heavier statements of the Neoclassical, or Monumentalist Movement (link in Italian). Just behind this main thoroughfare, you can still see the “economic houses” and the “very economic houses” built by Mussolini to win support from the poorer classes—practical, essentialist buildings that were meant to provide all the basic amenities at a low cost, but which still required more money than the regime had. What remains today of this obsession for architecture is a visual dictionary of the 1920s and 1930s architectural lexicon, making Predappio a period-movie director’s dream. In recent years, the mayor has supervised the restoration of these buildings, which are all currently in use.

Now this architecture, and Mussolini’s hand in it, is presented to visitors as an “open air museum,” peppered with explanatory signs and leaflets, giving the first hint that Predappio wants to go from being seen as Mussolini’s shrine to a town that acknowledges its history without openly endorsing it.

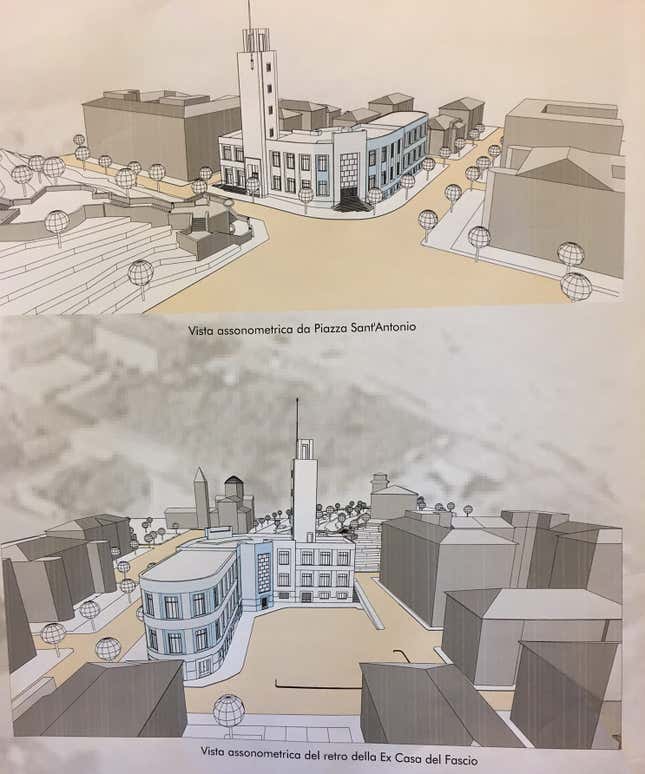

At the very end of the main road is the red and white Casa del Fascio, or “Fasci House,” a Rationalist gem, badly in need of repairs. This is where the Museum of Fascism is to be housed, with a scheduled opening for 2019.

“Predappio has an important role: here, Mussolini was born, and here, he is buried. We cannot pretend this is not the case,” Frassineti says. But, he adds, “I believe that we have a duty to tell Italian history in its entirety.”

∞

Growing up in Bologna and Florence—two cities awarded the Gold Medal of the Resistance, an honor given to the cities that fought most valiantly against fascism and the invading German troops —I spent more time studying anti-fascism at school than I did fascism itself. Many Italians have only a cursory understanding of the crimes perpetrated in Mussolini’s name, and of the ideology he touted.

This is because for decades, Italy has tried to avoid the debate over fascism’s legacy in the country. Unlike Germany or South Africa, for example, which have a number of public spaces that invite people to reflect upon the horrors of Nazism and apartheid, Italy has avoided similar historical reflections.

A few things have contributed to this eagerly pursued amnesia. To start, Italians have chosen to focus on the resistance movement that helped to overturn the fascist regime rather than on its supporters, explains Giulia Albanese, professor of Contemporary History at Padova’s University. And Italy has also avoided reckoning with its own crimes by concentrating on “the comparison with Nazism, which has always been used to justify, and minimize, fascism’s crimes,” making what happened in Italy look more benign, Albanese says. Add to all this the fact that Italy became one of many pawns during the Cold War, meant to fight a further spread of communism, delaying indefinitely the day of reckoning.

The desire to sweep the horror of the regime under the carpet has opened the country to revisionism and indifference. And in spite of a law which criminalizes reviving the Fascist Party, attempts at whitewashing the country’s history are treated with surprising tolerance.

∞

The choice of the birthplace of Mussolini as the site for Italy’s only Museum of Fascism to date has caused a storm of controversy. Many fear the museum could turn the town into even more of a shrine to fascism.

“Predappio and Mussolini’s tomb have become the holy site of nostalgia” for neofascists, one of the museum’s critics, the Alfred Lewin Association, said in a statement issued in March last year. The nonprofit research center and library, based in nearby Forlì, honors a German Jew who sought refuge (link in Italian) in Italy only to be executed in 1944, together with 16 others, by Nazi soldiers. It feels that locating the museum in Predappio “fits in the fascist narrative of a ‘destiny man.’”

“We are not just against it, we are indignant,” says Tamer Favali, head of a local chapter of the National Association of Italian Partisans. “If they can build a museum that also gives prominence to the resistance against fascism, to those who lost their lives, then maybe it can become a vaccine, an anti-dictator vaccine, and we will not oppose it. But how do we make sure there is a strong, constant control of what is being displayed?”

Carlo Ginzburg, one of Italy’s most prominent historians, wrote (link in Italian) that the museum “would further identify fascism individually with Mussolini,” and once again absolve the whole country from its support and participation in the establishment of fascism.

“Italy cannot be asked to shoulder Predappio’s problems in this context,” says Albanese, the historian. “What there should be is a nation-wide, or at least region-wide historical trail that shows what fascism was and did, to counter the Italian tendency towards historical denial.”

Proponents of the museum, on the other hand, believe it will help Italy confront its past without making excuses for it. “We must become capable of talking about fascism as if it were any other historical time, without feeling compelled to add… things like ‘Oh, but it became truly bad only after Nazism entered the fray,’” says Marcello Flores, professor of History and Human Rights History at Siena University, who has been coordinating the preliminary plans for the museum. “We must become secular enough to be able to talk about fascism in all its aspects, without fear and without political expediency,” he argues. “Our democracy was born out of that disaster.”

∞

Despite the criticisms, the project is moving forward. Funds for the estimated €6.5 million project will be raised by the government, and the EU announced at the end of last year that it would contribute €2 million towards the endeavor.

Far from the heated disputes among historians, the idea of a national museum of Fascism is supported by many local citizens, tired of living under the dark shadow of Italy’s dictator and of his contemporary supporters. For Paola Meloni, a 46-year-old lawyer from Predappio, having the museum would be a relief: “Predappio could really do with an attraction that is more neutral. We had hoped to market ourselves for our local wine, but it has not been enough. I would welcome a good historical museum here,” she says.

In the meantime, Predappio lives on in its parallel reality, where anybody can openly buy a fascist uniform.