The struggle of literary translation is mostly cups of tea and an agony of synonyms, but swords will be drawn at noon this Saturday when I will be going head to head with Frank Wynne, as we defend our translations of a specially commissioned short text from Congolese writer Alain Mabanckou.

It's scary stuff. I haven't seen what Frank's written and he hasn't clapped eyes on my version, but the event's curator and chair, Daniel Hahn, has got his mitts on both – and he's doing little to allay our fears. While conceding there are no whopping discrepancies of meaning in our translations, he has gleefully divulged the following piece of data: "Of the 56 sentences in the story, there is precisely one which is rendered just the same by both translators. That one sentence, incidentally, is the line of dialogue that goes: "Really?""

Gulp. Only one word, a question mark and a set of speech marks in common? And there was I anxious that Mabanckou's brilliantly witty but sparse and snappy tale of Sakiamboundou, a gullible wannabe ladies' man, might not leave much room for variation. I should have known better. As Daniel so eloquently puts it, "translating is an act of writing, but one where incredibly stringent rules apply" – and you wouldn't expect two authors to produce identical responses to a written challenge, now would you?

Of course, we translators have to find elbow room within linguistic and syntactical constraints while simultaneously jumping through idiomatic hoops. But I reckon our real work goes on beneath the surface. We may be doing grammatical somersaults, but all the while the "voice" we are giving birth to in a new language is creeping up on us, whispering in our ear.

If this trans-slam business (as I'm dubbing the Live Translation event) is hair-raising for Frank and me – having our translating ticks laid bare for public scrutiny feels uncomfortably exposing – whatever must Mabanckou be thinking? As an author with an international readership, he makes a leap of faith when he signs up to having his works translated into foreign languages and cultures that may be light years from the worlds of the Congolese characters he depicts. Yet here two allegedly proficient practitioners, both operating within the same language, are making different choices at every single linguistic crossroads.

Mabanckou is better placed than most to judge which voice might best capture or resonate with his own. As professor of Francophone Literature at UCLA he navigates these issues on a daily basis. Not that he should have to be his own gatekeeper. After all, isn't it the job of publishers and editors to administer the air and gas when a work of literature is being linguistically reborn? And don't readers the world over consistently recalibrate their brains to react with landscapes of words and images that differ in every way from their personal experience? In that act of reaching out, don't they also discover what they share with characters they might otherwise never meet?

Let me give you a concrete example. I translated a first novel by the young French-Algerian writer Faïza Guène, Just Like Tomorrow. It was an unexpected hit in Hong Kong, where the high-rise experience of slang-riffing North African immigrants in the French metropolis might seem remote, but where teenagers do still transcend their surroundings by falling in love. Conversely, East Africa is one of the few regions where Harry Potter hasn't been translated, because of the real powers still associated with witchcraft.

Back here, Mabanckou knows something must be going right because his most recent novel to reach British turf, Broken Glass, proved (in Helen Stevenson's exceptional translation) a strong contender on the shortlist for this year's Independent Foreign Fiction prize.

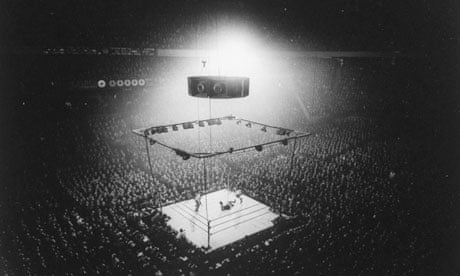

Meanwhile, Saturday looms terrifyingly. Or, as Frank put it: "Great – Congolese French translated live – sure you don't want us to simultaneously walk a tightrope?"

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion