Women who write smart, demanding novels are perceived by critics as strange and unnatural, "like a dog standing on its hind legs", the novelist AS Byatt tonight told the Edinburgh international book festival.

Byatt, who won the Booker prize in 1990 and was shortlisted for last year's award, said it was very hard for women to be accepted if they wrote intellectually challenging fiction. "If you are trying to think, there are always reviewers who take the attitude that it's like a dog standing on its hind legs, as Samuel Johnson put it: it would be better if you didn't do it."

The British novelist has been vocal in her criticism of sexism in the literary world, and also hit out at the Orange prize, which is limited to only women novelists. "The Orange prize is a sexist prize," she said. "You couldn't found a prize for male writers. The Orange prize assumes there is a feminine subject matter – which I don't believe in. It's honourable to believe that – there are fine critics and writers who do – but I don't."

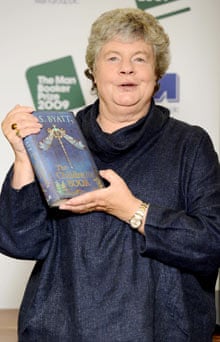

Byatt was tonight awarded the James Tait Black Memorial prize, Britain's oldest literary award, for her latest novel, The Children's Book, pipping Hilary Mantel's Wolf Hall to the post. Previous writers to receive the award include DH Lawrence, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene.

Other writers disagreed with Byatt on women's writing, with the Costa prize-winning author AL Kennedy calling her views "possibly slightly dated".

"I certainly, I would imagine, fall into the intellectually challenging box, and I don't think it has been particularly difficult because I am female. I don't think it is an easy thing to write and expect to be commercial, even if you are from Venus and a hermaphrodite."

Ian Rankin agreed: "I don't think it's a gender thing. I think [Byatt] should stop reading the critics and start enjoying the sales — and the adulation of the crowds who obviously so enjoyed seeing her at the Edinburgh book festival."

He added: "As a reader I would say it was false. I did my PhD on Muriel Spark, the most intellectually demanding writer I know; there is no finer surgeon of the human heart than her. And she was taken seriously, she was reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement and the New York Times. And from a crime perspective, women have always been seen as better than men. Recently Patricia Highsmith was voted best crime writer of all time."

John Carey, professor emeritus of English at the University of Oxford, who was also awarded a James Tait Memorial prize today for his biography of William Golding, denied that intellectual novels by women were not taken seriously by his fellow critics.

"I very much admire AS Byatt's intellectual scope. In fact it's the literariness – though her pastiches are wonderful – that I like less. She is fantastically clever and when she's on about ideas she is astonishing. If one looks at 19th-century literature and intellectual scope, it's George Eliot … and Elizabeth Gaskell. Compared with them, Dickens is just a fantasist. So in short, I think she's not right on this one."

Byatt, who won the Booker for her novel Possession, recalled how her publishers had tried to remove the chunks of "Victorian" prose and poetry from the book. "I wept and wept," she said. "No one could have been more surprised than me that it did so well. I thought it was a niche book for academics. Which shows that you should always write a romance."

The Children's Book charts the fortunes of a group of interconnected families from 1895 to 1919; some of its characters recall real figures such as E Nesbit and Eric Gill. But, she said: "My books are not genre historical novels." She added: "But I love Hilary Mantel's novel [Wolf Hall, about the 16th-century statesman Thomas Cromwell], which is nearer a genre book than The Children's Book, but nonetheless transcends that category."

Byatt spoke about her next novel, which will cover a period not yet charted in her fiction: the 1930s and 1940s. "My next novel was going to be about two lady psychoanalysts who study with Freud, up to the war." She added that she had decided to fit in another interest of hers, the surrealist movement. "But part of my problem with the surrealists is that I dislike so many of them."

She also spoke of her "suspicion" of memoir as a form: a form that her younger sister the novelist Margaret Drabble – who spoke at the festival on Thursday but was notably absent from Byatt's event – undertook in her 2009 book The Pattern in the Carpet, about the writers' aunt Phyllis.

Without referring specifically to Drabble's book, she said: "However well you write about your friends or family you diminish them," she said, "and it haunts me." She added: "I am a tarnished person, because you can't write a novel like The Children's Book without reading a great number of memoirs, but I can't see myself writing one and I certainly don't rush out and buy one unless I have to do so for research."

Women's writes

The subject of female writers and their place in the literary canon has often provoked controversy.

The spotlight was fixed firmly on the subject this year when Daisy Goodwin, TV producer, writer and chairman of this year's Orange prize for women's literature, complained of the depressing number of stories of victimisation and grief that had been submitted.

In her diatribe against "misery lit" she said she found very little wit and no jokes. "If I read another sensitive account of a woman coming to terms with bereavement, I was going to slit my wrists," she said.

Authors Toby Litt and Ali Smith sparked controversy, too, in the introduction to 13, a collection of poetry, short stories and extracts from novels.

They said: "On the whole the submissions from women were disappointingly domestic, the opposite of risk-taking – as if too many women writers have been injected with a special drug that keeps them dulled, good, saying the right thing, aping the right shape, and melancholy at doing it, depressed as hell."