Here's a modest proposal: what if the government took it on board to promote a reasonable, sane grasp of risk, security, and probability? Or, if you're a "Big Society/Small Government" LibCon, how about a more modest mandate still: we could ask the state to leave off promoting statistical innumeracy and the inability to understand risk and reward.

Start with the lottery: in the US, its slogan is "Lotto: You've Got to Be In It to Win It". A more numerate slogan would be "Lotto: Your Chance of Finding the Winning Ticket in the Road is Approximately the Same as Your Chance of Buying it". The more we tell people that there is a meaning gap between the one-in-a-squillion chance of finding the winning ticket and the one-in-several-million chance of buying it, the more we encourage the statistical fallacy that events are inherently more likely if they're very splashy and interesting to consider.

This is the same reasoning that causes parents to run in circles squawking in terror at the thought of paedophiles stalking their kiddies, even as they let Junior ride in the car without his seatbelt – auto fatalities being orders of magnitude more common than random paedophile attacks. (Of course, the most likely paeodophile in your child's life is you or your spouse, or a close friend, relative, or authority figure.) Preparing for the unlikely while neglecting the (relatively) common is a terrible way to make the world safer for you and yours.

Banish the lotto? Wouldn't that mean losing all the lovely money extracted by way of a voluntary tax on innumeracy? Perhaps, but if getting rid of the lottery could give rise to a modest increase in common sense about risk and security, think of the society-wide savings in money not spent on alarmist newspapers, quack child-protection schemes, MMR scares and the like!

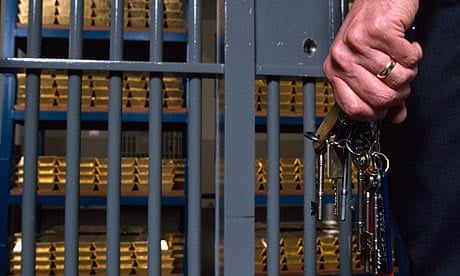

Once we get rid of the lottery, let's attack the banks. It's not bad enough that they collect enormous bonuses at public expense while destroying the economy; they also systematically disorder our capacity to understand risk and security through an ever-more-farcical stream of "compliance" hoops and bizarro-world "security" measures!

For example, my own bank, the Co-op, recently updated its business banking site (the old one was "best viewed with Windows 2000!"), "modernising" it with a new two-factor authentication scheme in the form of a little numeric keypad gadget you carry around with you. When you want to see your balance, you key a Pin into the gadget, and it returns a 10-digit number, which you then have to key into a browser-field that helpfully masks your keystrokes as you enter this gigantic one-time password.

Don't get me wrong: two-factor authentication makes perfect sense, and there's nothing wrong with using it to keep users' passwords out of the hands of keyloggers and other surveillance creeps. But a system that locks users out after three bad tries does not need to generate a 10-digit one-time password: the likelihood of guessing a modest four- or five-digit password in three tries is small enough that no appreciable benefit comes out of the other digits (but the hassle to the Co-op's many customers of these extra numbers, multiplied by every login attempt for years and years to come, is indeed appreciable).

As if to underscore the Co-op's security illiteracy, we have this business of masking the one-time Pin as you type it. The whole point of a one-time password is that it doesn't matter if it leaks, since it only works once. That's why we call it a "one-time Pin." Asking customers to key in a meaningless 10-digit code perfectly, every time, without visual feedback, isn't security. It's sadism.

It gets worse: the Pin you use with the gadget is your basic four-digit Pin, but numbers can't be sequential. This has the effect of reducing the keyspace by an enormous factor – a bizarrely contrarian move from a bank that "improves" its security by turning this constrained four-digit number into a whopping 10-digit one. Does the Co-op love or loathe large keyspaces? Both, it seems.

It's not just the Co-op, of course – this is endemic to the whole industry. For example, Citibank UK requires you to input your password by chasing a tiny, on-screen, all-caps password with your mouse-pointer, in the name of preventing a keylogger from capturing your password as you type it. This has the neat triple-play effect of slicing the keyspace in half (and more) by eliminating special characters and lower-case letters; incentivising customers to use shorter, less secure passwords because of the hassle of inputting them; and leaving the whole thing vulnerable to screen-loggers that simply make movies of which keys you mouse over.

But I quit Citibank, and I still use the Co-op for my commercial banking out of some bloody-minded, bolshy commitment to "good" banking, even though they require that foreign drafts be requested by means of faxes on headed paper (neither faxes nor headed paper being any sort of security system) and so on. Possibly it's because they occasionally see reason, as when I opened an account with my wife and discovered that I could either bring certified copies of both our passports to a branch; or I could bring my wife and her passport to a branch. The fact that my wife didn't have to be present in order to get a certified copy was a difficult concept for the Co-op to master, but once it did, a compliance officer agreed that this meant I should be able to simply show up at a branch with both passports without throwing money at some rich solicitor for the privilege of getting his stamp at the bottom of a photocopy.

It wasn't easy – the branch staff couldn't believe that I had won an exception to this weird policy – but in the end, they opened the account for me. Now, like a mouse that's found an experimental lever that only sometimes gives up a pellet, I find myself repeatedly pressing it, hoping to hit on the magical combination that will get my bank to behave as though security was something that a reasonable, sane person could understand, as opposed to a magic property that arises spontaneously in the presence of sufficient obfuscation and bureaucracy.

The great irony, of course, is that all the banks will tell you that they're only putting you through the Hell of Nonsensical Security because the FSA or some other authority have put them up to it. The regulators strenuously deny this, saying that they only specify principles – "thou shalt know thy customer" – not specific practices.

Which brings me back to my modest proposal: let's empower our regulators to fine banks that create nonsensical, incoherent security practices involving idolatrous worship of easy-to-forge utility bills and headed paper, in the name of preserving our national capacity to think critically about security.

Even if it doesn't kill the power of the tabloids to sell with screaming headlines about paedos, terrorists and vaccinations, it would, at least, be incredibly satisfying to keep your money in an institution that appears to have the most rudimentary grasp of what security is and where it comes from.